Holt adoptive father Jason McBride discusses race and discrimination issues surrounding adoption and addresses the question: “Why not just adopt from the United States?”

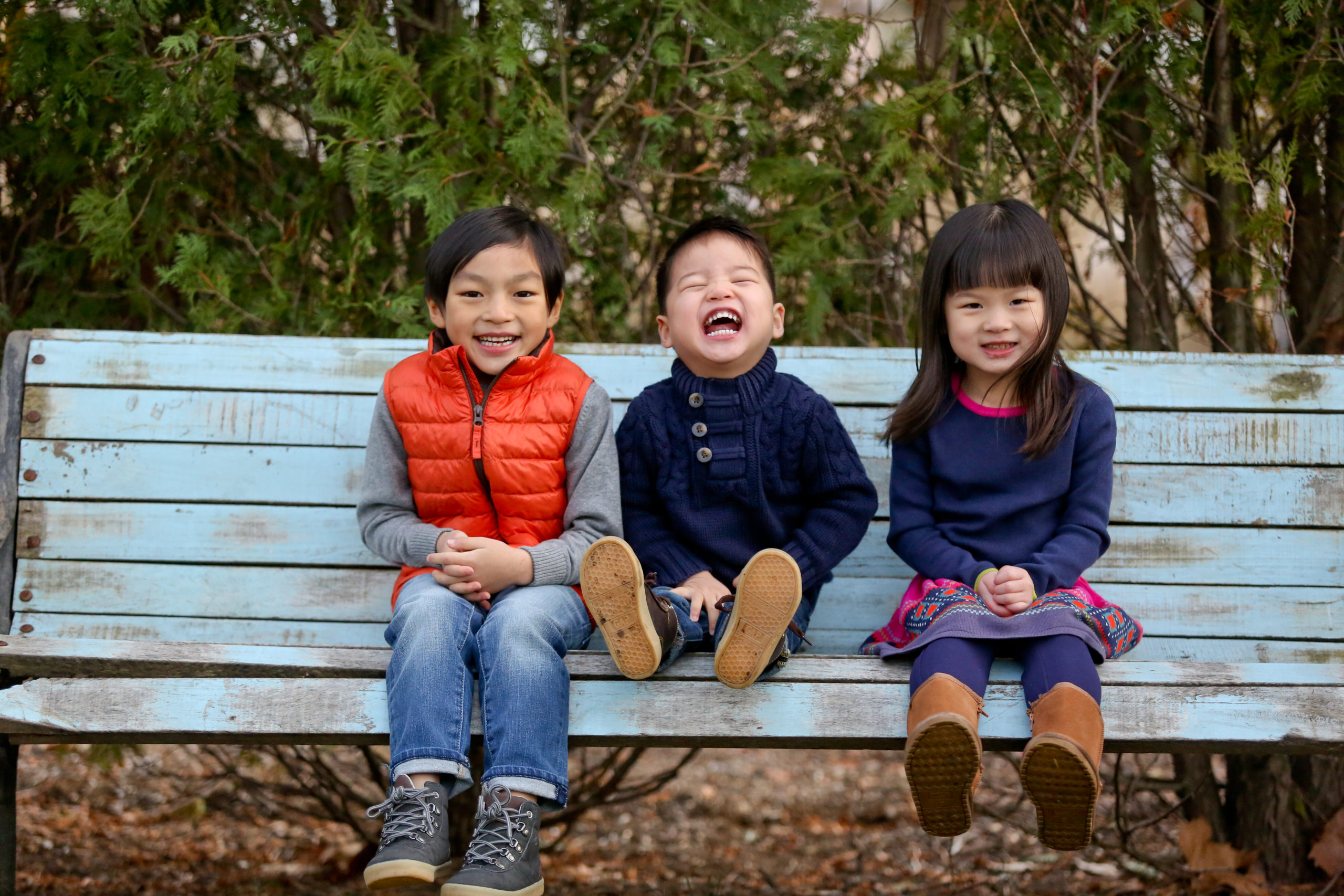

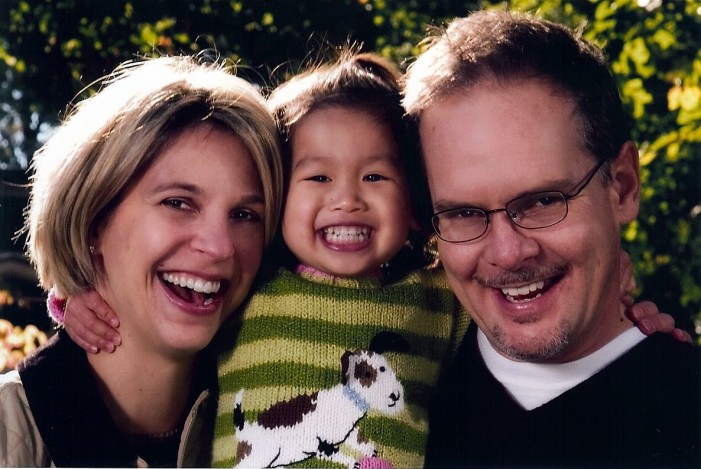

I’m the father of three children who were born and adopted from China. Like other adoptive fathers, I can appreciate the unique experience of having a mixed-race family. Publicly, whether at restaurants, parks or shopping malls, our family rarely goes unnoticed.

I enjoy the attention, not for lack of modesty, but because I like promoting adoption. I call this experience the “double take,” and parents of mixed-race families know it well. It’s the initial look we get in public, followed by a second look, before an approving smile as if to say “you’re good people.” While I don’t view adoption as charity, I do believe this reaction comes from a place of decency.

Unfortunately however, when it comes to children of international adoption, these same positive reactions in public don’t always translate into equally positive thoughts in private or on social media. In fact, many Americans discriminate against internationally adopted children because of misconceptions about the process. Worse, they discriminate on the grounds of a child’s birth country.

Imagine a child you care about. Maybe it’s your son or daughter, a niece, nephew or grandchild. Picture their smiling face looking up at you with all their innocence and beauty on display. Think of the wonderful qualities in this child. Maybe it’s a talent or a physical feature, or the way they cuddle with you during a movie. Really do it. Close your eyes for a second and imagine this child.

Now, imagine a stranger looking down at this child and bluntly saying, “I wish you were someone else.” How would such a cruel rejection of a person you love affect you? Worse, how do you think it would affect the child? What emotions would a comment like that create, both in you and in them?

Like all forms of prejudice, whether racial, religious or otherwise, discrimination against one’s country-of-origin is far too common.

This past November was National Adoption Month, a time for advocates to spread awareness. In a recent Facebook posting, where families were asked to contribute their adoption stories, many photos and inspirational comments were shared. But looking deeper, I noticed an alarming trend: The volume of people discouraged by children being adopted from other countries.

In the face of countless expressions of love, one person chose to say this: “I can’t help but feel sadness for the many children right here in OUR OWN COUNTRY that need loving families. More adoptions need to take place within the US. Those children need homes too”. This theme was fairly common throughout the comments section.

There’s little doubt, in the minds of most adoption advocates, that every child, regardless of his or her domestic or international birth status, deserves a loving home. Having experienced all of my children’s adoptions through the China process, I’m always fascinated by fellow advocates who’ve adopted elsewhere or domestically.

Likewise, it’s fairly common for advocates of any cause to support local charity. When we donate to food banks, we often prefer a church or mission down the street as opposed to the larger, national food drive. But this comment went further than a basic preference for one adoption process or another. It was rooted in cruel intention. In particular, it suggested children born in America are more valuable than children born elsewhere.

Notice the big, bold letters: “OUR OWN COUNTRY.” Think about that for a second. While the rapid-fire of comments sections are rarely the pinnacle of thoughtful dialect, imagine a person saying this directly to a child. “You, Sophia, look to be a wonderful little girl. However, it’s unfortunate your family didn’t choose to adopt someone who was born here instead.” If we wouldn’t tolerate this comment in person, why is it acceptable in written form?

While it’s far more common today, international adoption remains a mysterious topic for many people. Those of us who are familiar to the process have all heard the questions: How much was she? Did you get to pick him out? Are they really brother and sister? Or, my favorite from just the other week: Did you get a tax write-off for your business?

In fairness, it’s common for topics of unfamiliarity to be met with a degree of ignorance from those in second-hand positions. It’s only natural. In my case, as a Caucasian, I’d imagine a discussion about racial inequality with an African American with personal accounts of discrimination to be one-sided. As a male, I can hardly understand the real humiliation of gender bias. Though I’m concerned, I can’t relate.

Internationally adoptive parents understand this reality and do their best to avoid a constant state of offense. However, when it comes to the dignity and feelings of our children and to the core question of why they’re family, we shouldn’t be silent. In raising awareness for this year’s National Adoption Month, we should take a closer look at these open examples of discrimination being directed at our children.

Saying it’s better for one child to be adopted over another, because of a child’s unchosen birth country, is discriminatory and wrong. It cuts at the heart of that child’s identity, stares them in the face and states they’re inferior to others. It misrepresents the welcoming spirit of America and misunderstands the reasons for multiple adoption processes. Above all, it’s incredibly hurtful to millions of children who deserve better.

Jason McBride | Haddonfield, New Jersey

Adopt From China

Holt has three adoption programs in the China region. Learn about children who are waiting for families!

Seriously great article Jason! Eye opening…the section on closing your eyes – picturing – really drives the entire point home…no matter who a person is reading this…that point itself doesnt discriminate.

As a mother of 3 biological children and 4 children who were adopted internationally, I’d like to thank you for this article. It is very encouraging, and I agree with this article 100%. Thank you.

This article was so thoughtful and so needed. I get asked the “why not America” question more than any single other question. Thank you so much for putting my thoughts to words!

Thank you for your excellent article. We adopted infants from Korea back in the 80’s and early 90’s. We are now adopting a teenager from Thailand. The tide has definitely turned. More people seem to be critical of international adoption. The points you made are excellent and make for a good response to that question of “Why not domestic?”

Thanks for a thoughtful article. I am the mother of 9 children, four by birth and five more from adoption. One is from the US, two from So. Korea, one from Colombia, SA and the last from Vietnam. Even our social worker in Montana with whom we had already completed 3 adoptions asked us why we would take this 14 year old from Bogota, Colombia when we could get an older child here. I was working for an international agency at the time so I saw his sweet face in a newsletter seeking homes for the always harder to place older child. I said to her and meant it “he is a child who needs a home. How is that different than any other child”. I often wondered if she thought about my answer before she said that to another perspective adoptive parent. My son is 44 years old today, has a beautiful child of his own, my grandaughter, has two masters degrees in taxation accounting, and is a wonderful addition to our family. I love him very much and so did his father. He had little chance of a decent life in Colombia during those years. I have traveled to Colombia three times because of him and that was also a gift. That social worker’s words stung and that is why I remember them. Thanks for writing.

Excellent article and professionally written, Jason. I too have a beef with American who ask why people don’t adopt “one of our own”. They forget that it was blind chance that they themselves were born in this country.

I wrote about this on my own blog. https://mineinchina.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/we-need-to-take-care-of-our-own/

The two really aren’t in competition. There are far more children adopted through our domestic programs than there are internationally. Adoption through foster care is on the rise while international adoption is declining. I think that people have the perception that there are more international adoptions than actually occur because often children adopted domestically aren’t as “visible” as the children adopted internationally. Also, the high profile international celebrity adoptions come to mind for people as causing it to be “trendy” even though the numbers don’t bear that out in reality.

I have 8 children who hold my heart as Mom. One joined me thru birth. 3 were born to other mothers in S. Korea and are now grown or entering her teen years, One is now grown in Romania and was not able to legally join us, 2 have been foster children and one is now held in my heart as a grandson since my heart holds his mom as a daughter. Life’s journey has many twists and turns. When we can all truly be one human race instead of belonging to a race, country, state…Jesus will smile! Keep on educating others as comments are shared and understand that when your children are Asian and in America- these comments are shared by peers, teachers, other adults…when you are not there to shield them from them. Keep conversations going at home thru heartfelt humor and love, (avoid sarcasm). Great words and thank you for sharing them!

I do not know how many times I have been asked why I did not adopt an American child. My thoughts were, “What business is it of yours?”; but I politely attempted to answer the question. Thank you for the article. It helped me clarify my thoughts as to why I found this question so offensive.

Thank you for this insightful article. I have no personal experience with adoption, but I think it is a beautiful and wonderful thing for families. We have friends who tried to adopt from this country, but there was red tape for years-they adopted a beautiful girl from over seas with no regrets instead. I also went to church with several foster families. Some of them had these children in their home for years, and when they expressed an interest in adopting them, the children were snatched from the homes and placed elsewhere. It seems like America doesn’t place the welfare of children in “forever families” very highly, but then again, maybe this is just because of my limited knowledge.