Since the end of the Vietnam War, Vietnam has rebuilt its child welfare system. Holt served children through the country’s years of turmoil, and remains there today, partnering with the government and local organizations to serve children and families’ greatest needs — some of which are devastating, still-lingering effects of the war…

Four-hundred-and-nine. Four-hundred-and-nine children evacuated from Holt child care centers in Vietnam in the spring of 1975. The most notable being the Pan-America “babylift” flight out of Vietnam on April 5, 1975.

The flight took off from Saigon, current-day Ho Chi Minh City, just before the city was overtaken by the northern Vietnamese army.

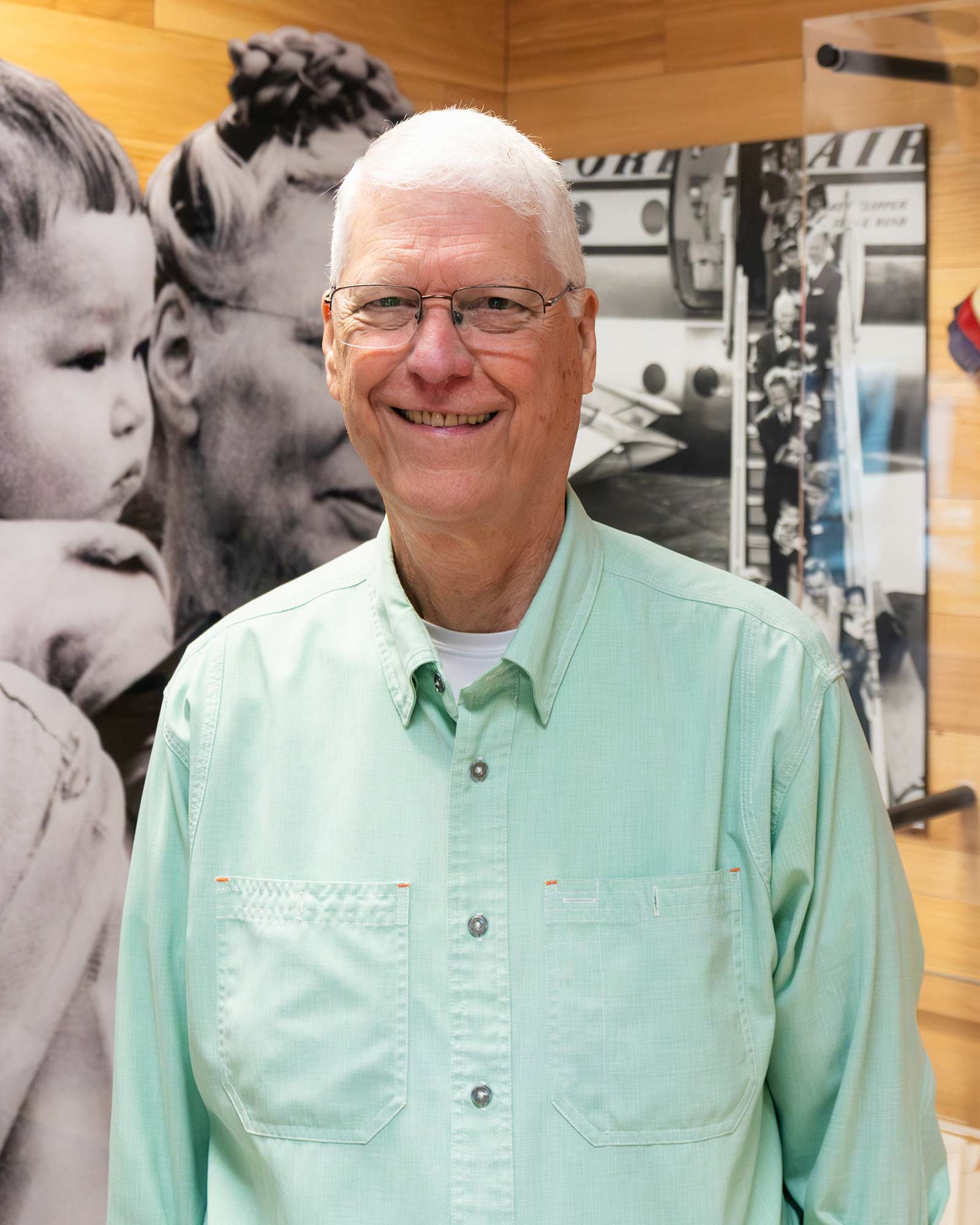

John Williams, who some years later served as Holt’s president, was working with Holt in Vietnam at the time of the airlift.

“All the kids had arm bands and leg bands on every limb to identify them so they wouldn’t get mixed up or lost,” John says of the children on Holt’s flight, most of whom were already matched with adoptive families in the U.S. at the time of the emergency evacuation.

“It was a long, long flight,” he recalls.

The plane flew from Saigon to Guam to Honolulu to Seattle to Chicago and finally New York. Beginning in Honolulu, and at each stop along the way, children united with adoptive parents who were extremely relieved to know their children had made it out safely. Because this wasn’t the case for everyone… An evacuation flight just days before — a flight the Holt children had nearly been on — tragically crashed several minutes after takeoff.

And just a few days later, John Williams – upon his return to Vietnam to help Holt staff evacuate – described the scene as “total anarchy in the streets — which were littered with uniforms and military equipment discarded by South Vietnamese soldiers fearing for their lives.”

This year marks 50 years since Operation Babylift, which was a defining and iconic moment in Holt’s history and legacy of caring for orphaned and vulnerable children.

But this flight was not the beginning of Holt’s work in Vietnam, and it certainly didn’t mark the end.

Holt Began Work in Vietnam

Holt first began working in Vietnam in 1972. The program primarily helped place children with adoptive families in the U.S. Because of the decades-long conflict in Vietnam, there were an estimated 900,000 homeless children in the country at the time.

Holt opened a child care center in response to this great need, providing the food and care that children needed while searching for permanent families for them through international adoption.

While some of these children had no known living parents, many of them did.

“Because of the conflict,” John says, “there were a lot of parents of children who were under great duress and thought their children would be better off in an institution because they were short of food and medical care.”

Realizing this, Holt’s team in Vietnam believed there should be alternatives or options other than international adoption for birth families to consider. Holt sought and secured a USAID grant to help reunify children from institutions with their birth families and empower families in poverty to continue caring for their children.

This is how Holt’s first family strengthening program began — in October 1974.

“The program was getting off to a very good start,” explains John, a former community development Peace Corps volunteer in Thailand and USAID agriculture and refugee resettlement officer in Laos, hired by Holt to manage the program. By January 1975, John says the number of families in the program was significant. But as it became clear mid-to-late March that Saigon would soon fall to the North, the program was cut short — and Holt’s team on the ground realized it was time to make plans to leave the country.

International Adoption Today

After the babylift, Holt couldn’t fully serve children in Vietnam again until 1989, when the Government of Vietnam invited Holt to help support and operate orphanages. In the ensuing years, Holt continued what they started before the babylift in 1975 — developing programs throughout the country that enabled children to stay in the loving care of their birth families.

International adoption from Vietnam to the U.S. occurred mostly off and on throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, as adoption legislation and country agreements changed, and was suspended in 2008. But in 2014, Holt was specifically invited to reopen the international adoption program to begin finding families for older children and those with special needs.

Today in Vietnam, similar to in the 1970s, most of the children in orphanages have living parents or extended birth family. But the reasons they remain in orphanage care are complex, from neglect or abuse to poverty or other crises that keep their families from being able to meet their child’s basic needs.

Child welfare centers are meant to provide temporary care for children — with the first goal being to reunify each child with loving birth family. Domestic adoption is pursued for the children who can’t reunify with their birth family. And only once these options are exhausted, international adoption is seen as the best opportunity for a child to grow up in a family, and not an institution.

Huong Nguyen, Holt’s Vietnam country director, explains that the government has strict criteria for who can and can’t be enrolled into orphanage care. “First, [the government] sees if the child has any kind of relatives who can take care of them,” she says. “And even if a child does come to live at the center, they have a plan for reaching out to the family to discuss when they are able to reunite the child and the family.”

Holt partners with both government-run and private child welfare centers across the country, providing caregiver trainings and other services to ensure the best care possible for the children who call these centers home.

While many of the children living in the centers are healthy and developmentally on-target, there is a much higher rate of children with disabilities and special needs living in institutional care than you’d find in the general population. The resources needed to care for a child with a disability are so much greater, and for a family already living in poverty, it can feel impossible.

While orphanages in Vietnam have a high rate of children with disabilities, this reflects a higher overall rate of children born with birth defects and disabilities than other countries — particularly in certain regions of Vietnam. And the reason for this is tied to events from over 50 years ago.

While it was their grandparents and great-grandparents who lived through it, even generations later, Vietnamese children are still feeling the physical effects of the war. One region that was especially impacted is the city of Hoi An.

Special Needs in Vietnam

Hoi An is a World Heritage Site and a beautiful coastal town that was once a significant Southeast Asian trading port in central Vietnam. It’s also the location of the Kianh Foundation – an incredible school for children with disabilities and special needs that’s supported by Holt sponsors and donors.

“The rates of disability are about 15 percent higher here,” says Hoang Pham, the program development director of the Kianh Foundation. And the likely cause is Agent Orange.

During the Vietnam War, American forces blanketed Hoi An and the surrounding region with the deadly chemical compound Agent Orange as they tried to fend off enemy troops. Thousands of innocent civilians died from exposure. And for more than two generations, women in areas once hit by Agent Orange have given birth to children with much higher-than-normal rates of physical and developmental disabilities.

But in this region with such high needs, there are few resources specifically for children with disabilities. That’s why the Kianh Foundation is so important.

The Kianh Foundation is an incredible, one-of-a-kind school for children with disabilities and special needs in Vietnam. Here, they learn life skills, have access to occupational and physical therapy — and grow and develop beyond what their families ever dreamed possible.

Every day, children with autism, Down syndrome, cerebral palsy and more come from the surrounding area to learn. But there are many more who want, and need, to come.

“We have a wait list of about 200,” Hoang says. “And the school can hold just 80.”

Through word of mouth, parents hear about the Kianh Foundation and desperately hope their child can have a spot. Attendance here is one of the greatest hopes they can find for their child to thrive, and have as independent a life as possible.

Throughout Vietnam, some families know about Holt and come to us for help. But the majority are referred to Holt by the local child welfare officials. Since the end of the conflict in Vietnam, and the reunification of the country, Vietnam operates through a strong centralized government, with local branches in each province and city. Holt works closely with the government, often filling in the gaps to provide help.

“We support the parts that the government cannot,” Huong says. This can be Holt donor-funded programs like the Kianh Foundation, as well as individual families throughout the country who are living in poverty.

Family Strengthening in Vietnam

Life in Vietnam has dramatically changed in the 50 years since the end of the Vietnam War. Economic reforms have led to greater prosperity for many people. But they have also increased disparities between rich and poor, rural and urban, and ethnic majority and minority families. Rural families often migrate to cities in search of work, putting children at risk of family separation, trafficking and exploitation.

Because of this, Holt’s family strengthening program – which began because of the needs children and families faced towards the end of the war – is active and strong today, serving more than 6,000 children and families across the country.

The Vietnamese government is quick to identify families living in poverty, however they often don’t have enough resources to provide the help children and families need to overcome it. This is where Holt Vietnam and Holt donors come in with education, single mother support and economic empowerment programs.

Helping Children Go to School

Helping children go to school is one of the foundational ways Holt donors help children in Vietnam. While some aspects of school are free to students, essentials like tutoring fees, school supplies and more can easily force a child to drop out sooner than they should. But with the right materials, and the caring oversight of a Holt social worker, thousands of children are excelling in school and on their way to graduation.

This begins at even the earliest ages, at Holt-supported daycares and preschools throughout the country. Many families living in poverty would never have the option to send their child to preschool, or even have a safe place to send their child while they go to work. And because of the nutritious meal these children receive each day at preschool, malnutrition rates have dropped significantly!

Older children receive the economic support they need to continue in their studies. And for older teenagers who may have already dropped out of school — a common occurrence for those who don’t pass the entrance exam for secondary school — Holt sponsors and donors help provide vocational training. By learning a trade such as hairdressing or running a food cart, they have the opportunity to learn a stable trade to support themselves.

And the support Holt donors provide stretches to help the entire family.

Strengthening the Entire Family

“They are the poorest of the poor,” Huong says of the families in Holt’s family strengthening program today. “They’re really in need of support, and we come at the right time, when they are at the risk of family separation or at the risk of children dropping out at school.”

Some families, out of desperation and poverty, will place their child in an institution if they aren’t able to provide enough food, medical care or other basic needs. But keeping a child in the loving care of their family is Holt’s biggest goal.

They are the poorest of the poor. They’re really in need of support, and we come at the right time, when they are at the risk of family separation or at the risk of children dropping out at school.

Huong Nguyen, Holt Vietnam’s country director

To do this, Holt’s family strengthening program comes around families living in poverty, equipping them with the tools to become self-reliant and independently provide for their children.

Once these families are identified with help from the local government, a Holt social worker will visit their home, get to know their family, understand their needs and begin to make a plan with them. For many families, this can mean helping them start small businesses or other income-generating activities like raising ducks or goats, opening a small shop, and more.

“We work with them to identify their potential and abilities, and make a business plan for them,” Huong says. “It’s very individualized. It’s a case management approach.”

In Vietnam, this often works in combination with providing education to their children. Or, if they are young, single mothers, Holt’s team in Vietnam also provides support and resources as they learn to care for their baby.

The result is that each family receives just the help they need to make their life better, overcome poverty and stay together.

While Holt’s work has grown and changed over the years, its goal and the dedication of Holt staff and donors have remained the same since John Williams first arrived in Saigon in October 1974 to help create Holt’s first family strengthening program.

Amazing Commitment in Vietnam

“The degree to which the staff, under tremendously stressful circumstances, did their job…” John trails off as he fights back tears, recalling the days leading up to the babylift in April 1975. “Their commitment was amazing.”

And this amazing commitment continues today from the Holt staff, and the Holt sponsors and donors who make Holt’s work in Vietnam possible — all for the sake of children and families in need.

Be the Bridge!

In order to keep serving all the children in our care, we need to overcome the funding shortfall by April 30.