On April 5, 1975, Holt evacuated exactly 409 children from Saigon in what has now famously become known as the “Vietnam Babylift.” As Saigon was about to fall to the North, Holt’s flight was one of several agency-arranged flights intended to evacuate children already in process to be adopted abroad. Fifty years later, we look back at this dramatic moment in Holt’s history through the eyes of one key figure who was on the ground helping to evacuate children in Holt’s care — former Holt president John Williams.

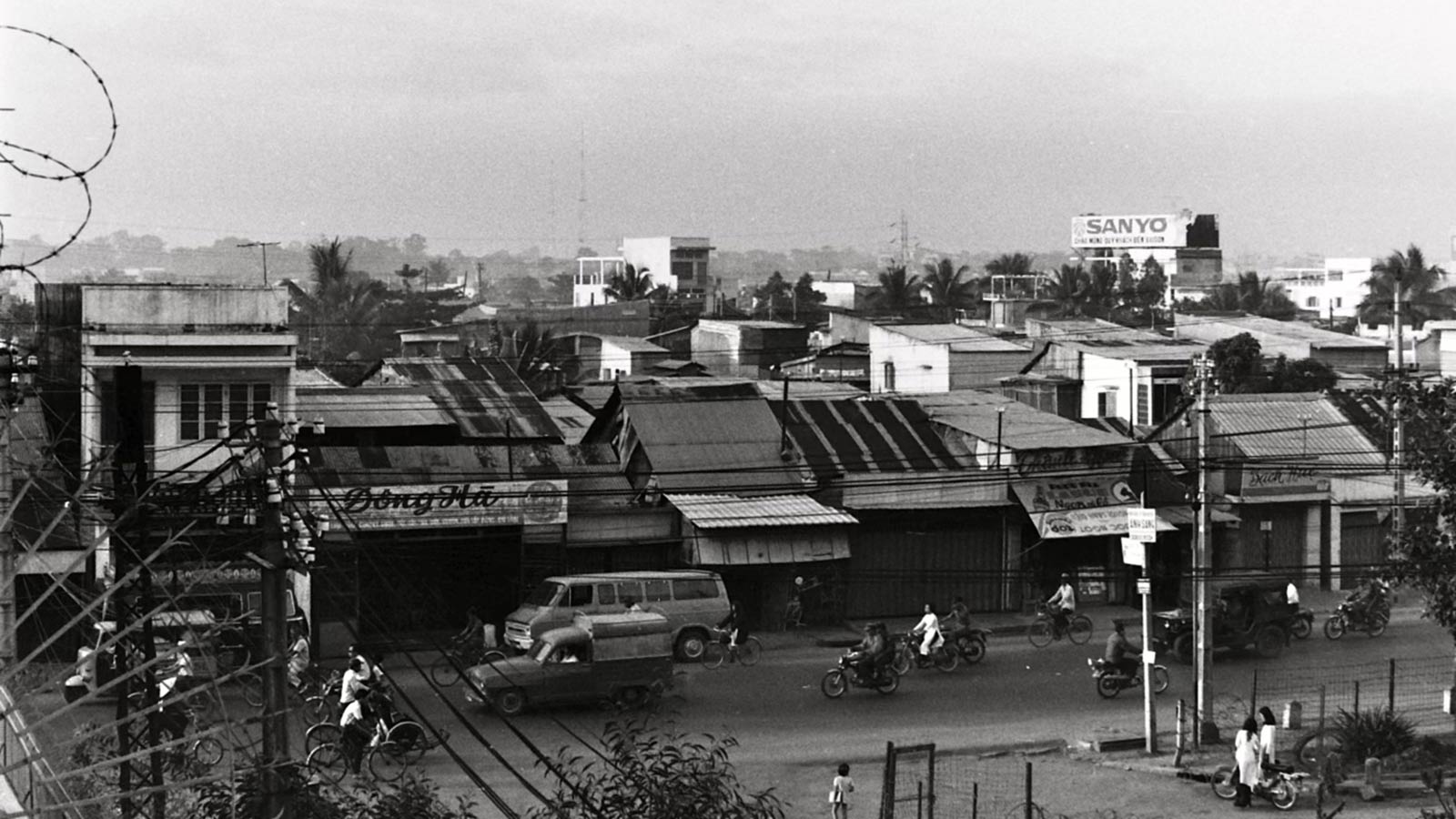

In the sweltering, suffocating heat of 1975, South Vietnam teetered on the edge of defeat.

Tensions had reached a fever pitch. The air was thick with uncertainty and fear.

Tens of thousands had already fled to Saigon, seeking refuge as North Vietnamese forces bore relentlessly through the countryside.

It was only a matter of time before the forces descended on Saigon.

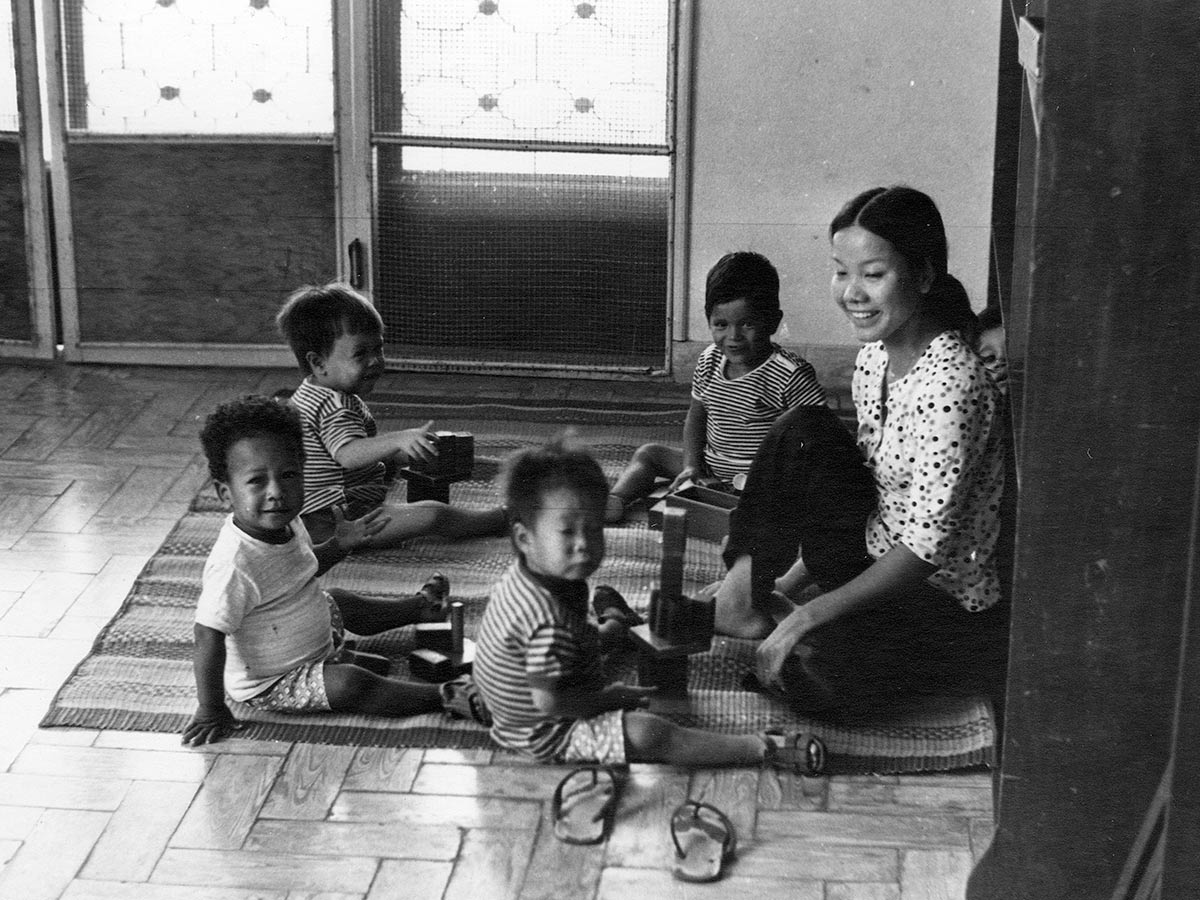

Just three years before, Holt International had come to Vietnam to help unite children with families through adoption. Holt’s team on the ground had also just begun to implement Holt’s first family strengthening program — empowering families at risk of separation to continue caring for their children.

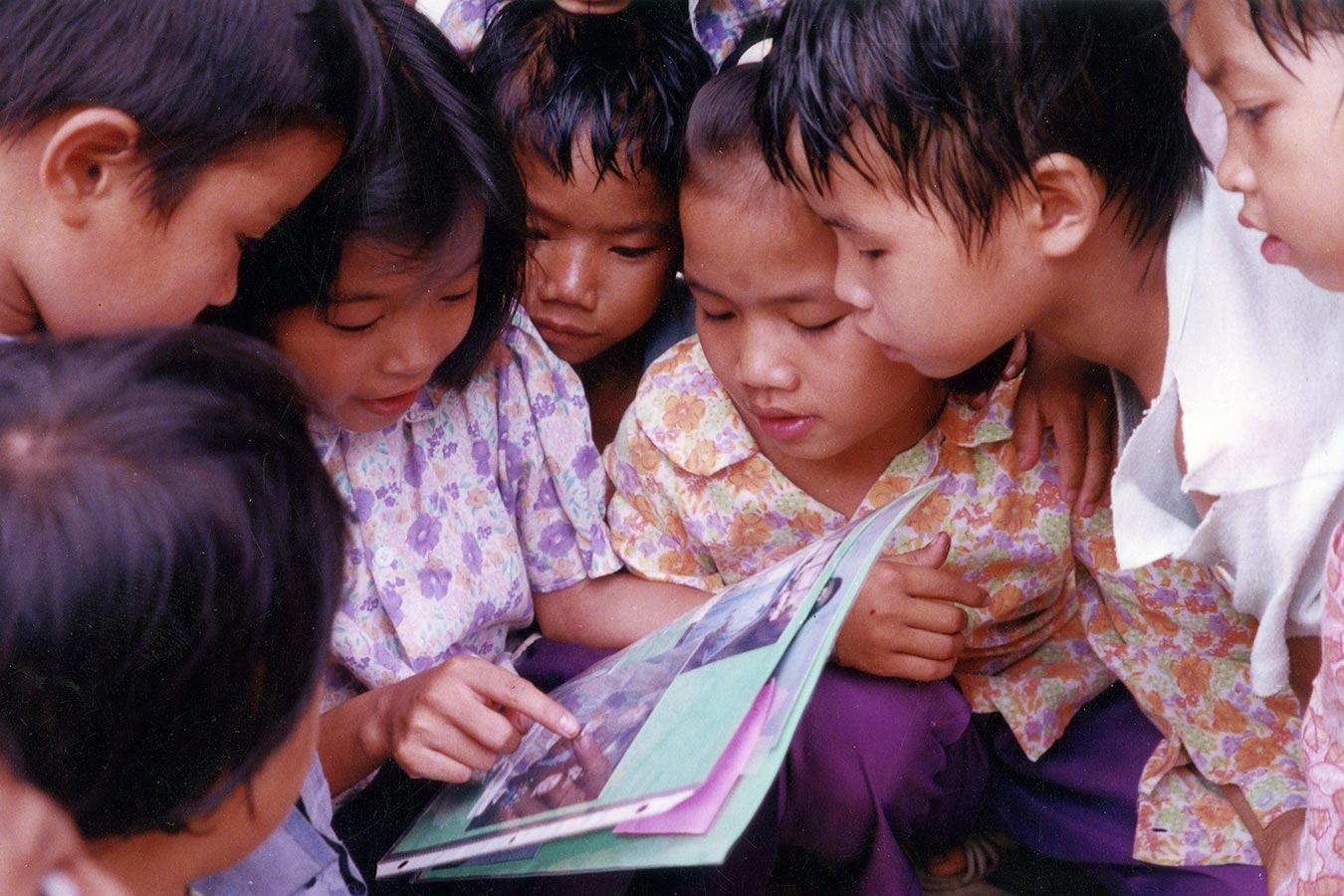

But as it became clear that Saigon would soon fall to the North, Holt’s team knew they needed to make an emergency plan for the children in their care. Even during this perilous time, foster parents and caregivers at Holt’s care center in Saigon continued to provide nurturing care for the children — some of whom carried the weight of uncertainty, aware that their futures hung in the balance, while others were too young to understand what lay ahead.

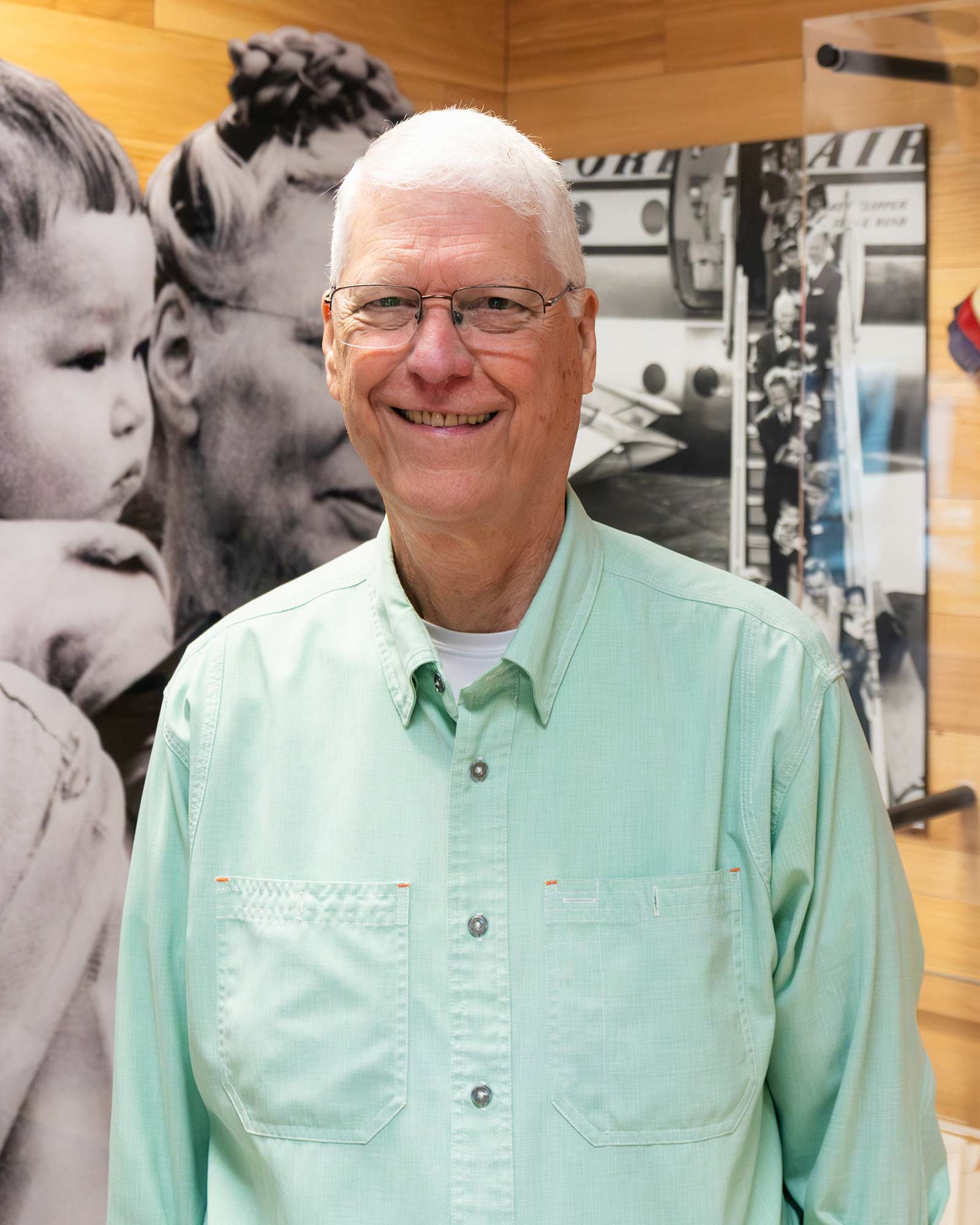

Called to Vietnam

In September of 1974, John Williams received a call out of the blue. On the other end of the line was David Kim, Holt’s deputy director at the time. John had never heard of Holt International.

“David shared with me that they were looking for someone to serve as a project manager in Vietnam,” John remembers. Holt had received a USAID grant to establish a family assistance program there, and he asked if John was interested.

John had spent two years in the Peace Corps in Thailand as a volunteer and seven working for USAID in Laos, where he met his wife. He had returned to the United States and was looking for a job.

After some time spent thinking, praying and talking with his family, John felt called to Vietnam. He signed a one-year contract … which turned into 28 years with Holt International. John eventually served as president of the organization for 10 of those.

Family Strengthening Efforts in Vietnam

“When I arrived in Saigon in early October 1974, there was no [family assistance] program. We had to design, start the program and get the word out,” John says. “Holt had primarily been an international adoption agency up to that point.”

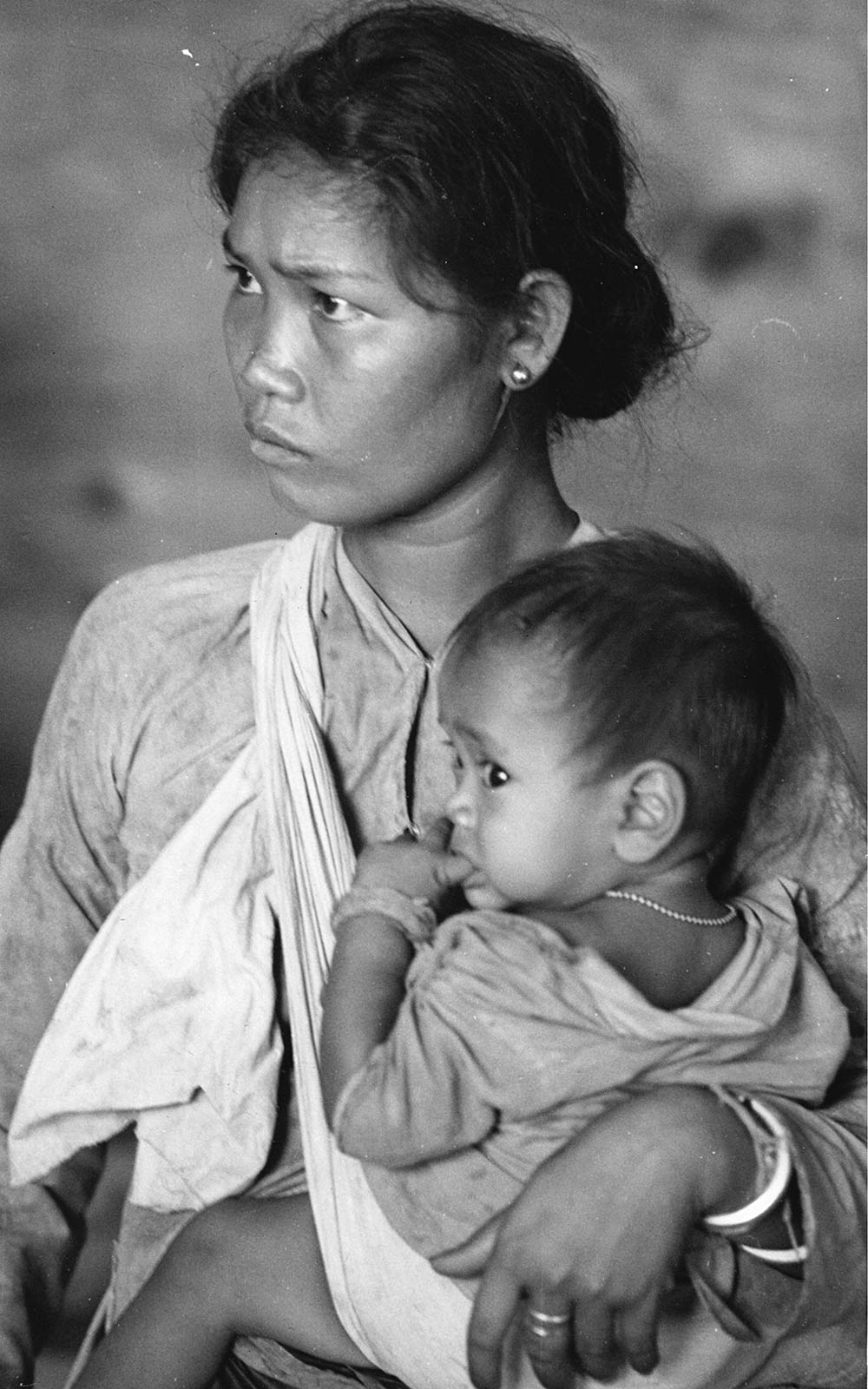

Holt began its international adoption program in Vietnam in 1972. Over time, Holt staff recognized that many families felt they had no option but to relinquish their children — in many cases, because poverty prevented them from being able to provide the care their children needed.

“They were seeing a lot of birth parents coming in saying they wanted to relinquish their child,” John says. “If given an alternative to consider keeping their family together, that’s what they were looking for. They just were under so much stress — their child was suffering from malnutrition, health issues, etc.”

And the formation of the family assistance program changed everything.

Once families realized they had a viable option to keep their families together, they no longer wanted to relinquish their children. Within a few months, Holt’s first family assistance program was thriving, providing families with a renewed sense of hope.

“It was much like many of the family strengthening programs today,” John explains. “The role of social workers and case workers was to determine what the interests, abilities and skills of the family were. My background as a Peace Corps volunteer was as a community development worker, meaning that it was all about finding out what the interests of the community or village were and helping them develop that interest into an income-generating program that created independence, not dependency.”

Some families in the program were supported in starting small businesses, such as sewing or tailoring, which required training and equipment. Others raised animals like ducks or chickens, providing sustainable food and income. The goal was to complete each family’s case within six months, helping them get on their feet and provide for their children, keeping the family together.

“It was the first time that Holt began to broaden its services to children with a list of priorities — preserve the birth family, domestic adoption, international adoption — with no one being better than the other,” John says, describing the model of service that Holt has long ascribed to, and later advocated for when we sent delegates to help draft the Hague Convention on the Rights of the Child. “It’s based on the best interest of the child.”

Tensions Rising in Vietnam

By January 1975, Holt’s family assistance program was growing and the number of families in the program was significant. But the atmosphere in Saigon had begun to turn.

“In early 1975, we began to hear rumors and stories of unusual military activity on the part of the North Vietnamese,” John recalls. “Holt, by that time, had the adoption program and the three centers in Saigon. We also had a childcare center in Da Nang, the central part of the country, and a relationship with an orphanage in Vũng Tàu, which we supported.”

In mid-March, John and other Holt staff went up north to visit Da Nang to check on the childcare center and assess the possibility of expanding the family assistance program.

While there, they were invited to an event at the U.S. consulate compound. A consular officer told them there was no cause for concern — there was no possibility that the North Vietnamese could reach Da Nang because of the Hai Van Pass blocking their path.

Ten days later, Da Nang was overrun by the North Vietnamese.

“When we realized that Da Nang was going to be overrun, we did manage to get all of the children evacuated along with the staff and get them evacuated down to Saigon,” John says. “There were tens of thousands of people who were fleeing south, and the population of Saigon began to grow tremendously. We weren’t sure what the final outcome would be, but it didn’t look good.”

“By the end of March, the embassy staff was being reduced, and thousands of Vietnamese were attempting to flee the country by any means possible,” John says.

With their connections to the U.S. embassy, John and his co-workers tried their best to stay informed on the situation. At one point, one official told them, “You better make your plans to get out.”

“So, we did,” he says. “We began making plans to get out.”

Preparing to Flee

Arrangements were made for Holt to charter a Pan Am 747 to evacuate all the children in Holt’s care.

“When it became apparent that Saigon was not going to hold and it was going to be overrun, it was not uncommon for desperate mothers to come to us, pleading for us to take their children,” John recalls.

As Holt staff spoke with each family, offering alternatives, the desperation of the situation was palpable. The families would do anything to save their children. But with Holt’s commitment to keeping birth families together when at all possible, the team declined to take in the children that had loving families, regardless of the unknowns that lay before them.

“We stopped accepting children a couple weeks before the final evacuation,” John says. “And we came under some criticism for that.”

As a newer member of Holt’s staff at the time, John shares that the decision not to bring more children to the U.S. spoke volumes about Holt’s integrity.

“I signed a one-year contract with Holt and if it hadn’t been for that experience, I don’t know if I would’ve stayed on with Holt or not,” John says today, looking back on his first dramatic months with Holt. “It said so much to me about Holt’s integrity and how careful it is. If a child is placed in our care and [is] going to be placed for international adoption — for all intents and purposes, that child does not have a good option to remain with a family in their birth country.”

Holt and other agencies began lobbying and requesting that visas and paperwork be expedited for children in the process of adoption. They appealed to both the U.S. and Vietnamese governments, and the request was approved — for Holt and several other agencies in Vietnam. Across all agencies, approximately 2,000 children were cleared for evacuation.

“Our flight was scheduled, the visas were approved and three or four days before we were scheduled to leave, the caseworkers began to spread out around Saigon,” John says. “We had maybe 250 children in foster homes scattered around Saigon, and so arrangements had to be made for them to be brought in time for the flight on April 5.”

The First Flight of the Vietnam Babylift

As the days grew closer to the scheduled April 5 flight, the Holt team was feeling the pressure.

“By now, the noose around Saigon was getting pretty tight,” John says. “There were occasional rockets coming into the city. The night sky was full of flares and tracers.”

A few days before April 5, the U.S. embassy notified Holt that President Ford had authorized U.S. military aircraft for the babylift. They were given the opportunity to be on the first flight, which was set to depart on April 4.

“We thought long and hard about it. In the end, we had already made arrangements for the Pan Am flight, and we felt good about those arrangements,” John says. “We were really encouraged to be a part of the April 4 flight. But the more we heard and the more we thought about it, we just didn’t feel comfortable with those arrangements. … We declined the offer.”

On April 4, at the time of the military flight, John and the Holt team were busy preparing for their own flight the following day.

“Here we are on April 4 and we’re frantic,” John says. “All of a sudden, we get word that the C5A — the first flight of Operation Babylift — had taken off and crashed. … Holt’s office was very near the airport. We could actually see the plume of smoke from our office.”

The plane had two decks — an upper and a lower, and tragically, many on the lower deck didn’t make it. A malfunction in the rear cargo door caused it to blow open, sucking the oxygen out of the cabin. Desperate to make it back to the airport, the crew turned the plane around. But it crashed just a few miles short of the runway in a rice paddy — killing 78 children and 50 adults. “A lot of people we knew were on that flight,” John says, his eyes growing misty as he sits in the Holt office, almost exactly 50 years later. “We didn’t have a lot of time to reflect on it at the time, but the thought crossed our mind, ‘Oh my gosh — by the grace of God….’”

Holt’s Flight Out of Vietnam

In the thick heat of April 5, 1975, the day arrived for Holt to evacuate children from Vietnam.

They proceeded with their arrangements to evacuate all the children in Holt’s care — a total of over 400 children. The Holt compound was full of children running around, while Holt staff frantically worked through paperwork. Over 250 of the foster children needed to be brought to Holt’s office for departure.

“The remarkable thing to me — so many remarkable things happened then — was that the foster parents were amazing,” John says. “With all that was going on, with all the stress and uncertainty that they faced, how much they cared about the children. … We didn’t lose a single child. Every foster family brought their child in that they were caring for.”

One image stands out in John’s memory — an image not too different from what our in-country staff still see today whenever a foster parent has to part with a child they have selflessly cared for while they waited to reunite with their birth family or join a family through adoption. It is always a bittersweet moment for these devoted foster parents, whether in the midst of war or on an otherwise peaceful day.

“One of the images that’s just seared into my mind,” John shares, “is as the busses were loaded, most of the busses had mesh on the windows — like screens or wire that you could get your fingers into and hold on — and as the busses were pulling away, a number of the foster mothers were clinging to the side of the bus to kind of get one last glimpse of the child they had cared for.”

With over 400 children in their care, they hurried to the airport and began loading the plane. Time was critical — the aircraft could remain on the ground for only an hour, and every minute cost thousands in insurance fees, totaling around $50,000.

Inside the 747, the upper deck had been transformed into a makeshift medical unit. Infants were carefully placed in baskets and boxes lined with blankets, ensuring their fragile safety for the journey ahead.

“We had four identification bands — two armbands, two leg bands — for every child with their information on it to make sure that if one came off, there would be redundant systems to keep track of who was on who,” John explains.

All the children were loaded, 409 in all, along with 50 adults. And with a deep breath, the plane took off.

“There were a lot of cheers and tears as we took off out of Saigon.”

Operation Babylift Complete

The flight first landed in Guam, then Hawaii and then Seattle. The arrival was late — around midnight, but many people had gathered at the airport to welcome the flight.

The door of the plane was opened, helping dissipate the pungent cabin air.

It had been a long ride.

“The children were taken out one by one — not rushed out,” John says. “Nametags were checked and accounted for — double-checked and triple-checked by the Holt staff there.”

John recalls that many of the adoptive parents were waiting to welcome their child at the airport in Seattle, while for others, the flight continued on to Chicago and then New York. With each landing, a family was united with their adopted child for the first time.

A Hasty Return to Vietnam

Rubbing their sleepless eyes, John and his colleagues that traveled with him on the flight had made it back to the United States.

But it wasn’t over.

John and two of his Holt colleagues, Bob Chamness and Glen Noteboom, knew they had to go back for the staff that had been left in Vietnam. And they made their plans quickly.

“We were now concerned about the Holt staff — the Vietnamese staff — in Vietnam,” John says. “We made arrangements three days later to return to Saigon. In those three days, watching television in the States, things had deteriorated tremendously. Things were changing very, very quickly.”

With uncertainty hanging in the air, the three set their course for Vietnam.

“I’ll never forget — when we flew into Saigon, we were still at 30,000 feet and then they made a very tight spiral landing down to the airport in Saigon,” John shares.

Their corkscrew landing on the airfield was much like the whirlwind to come. The city was in chaos. On their drive back to the office, the streets were in complete anarchy.

“There was very little law and order to be had,” he says.

After returning to the Holt office and strategizing with the staff, the team got to work compiling records to be flown out of Vietnam.

“We were also concerned about the records — knowing how important the child histories are,” John says. “That was another thing that impressed me about Holt, that they made every effort to document the background and circumstances for each child coming into care. We chartered a DC3 aircraft to take out all the boxes and boxes of childcare records and medical histories for the kids.”

An Overflowing Operation

The U.S.-sanctioned babylift flights were intended for children with approved parole visas in the process of adoption. There were originally 2,000 children approved for the airlifts, including the 409 children who were in the care of Holt International.

“I don’t know how many children were eventually flown to the U.S. and other countries under the name of Operation Babylift. I’m pretty certain that the number exceeded the [number] that it was designed for,” John says.

Between April 2 and April 29, it is estimated that over 3,000 children were evacuated, joining families in the U.S., Europe, Australia and Canada.

“I can only speak for Holt, my experience in Vietnam and the way that Holt conducted its affairs during that period of time,” John says. “The integrity of the program and the care and carefulness that Holt social workers took to document, provide care, and provide alternatives to birth parents, the efforts to research the background, to make sure that if a child was placed for international adoption, that there were few, if any, viable options for that child to remain in a safe and secure family setting in Vietnam at that time.”

Time Running Out in Vietnam

As the levels of desperation and panic rose, the plan to evacuate Holt staff became imminent.

“We developed a list of our staff that we believed would be vulnerable under a North Vietnamese regime because of their close ties — either having worked with the U.S. military before or government agencies before,” John says.

They made arrangements for those who wanted to leave — around 150 Holt staff and their immediate family members — to be evacuated on a flight leaving on April 27. On April 25 and 26, Holt began transporting staff members to the airfield.

“Someone from the embassy had left us their car which had diplomatic license plates on it — and it didn’t get stopped,” John says of the military and police personnel who were turning people away, regardless of their papers. “With that one car, we ferried people to a holding area in the air base where they were told to wait.”

After many hours, all 150 Holt staff along with their family members had made it to the airfield, along with hundreds of boxes full of childcare records for the DC3 chartered flight.

A Promise for Evacuation

It was April 27 and the DC3 was loaded with all of the child histories. There hadn’t been any fixed-wing airplanes that had taken off for several days.

“We wanted to wait till [the Vietnamese staff] had been taken out — to make sure they got out — but we were told by one of the U.S. officials, ‘You’ve got to leave now. If you don’t leave now, the likelihood of you getting out is very slim,’” John recalls.

They were promised by an official with a connection to Holt that the Vietnamese staff would make it out. Thinking that he’d have the Holt staff’s best interests in mind, they took him at his word.

“One of the hardest decisions that any of us ever had to make was telling our staff, ‘Okay, you’re here,’” he says. ‘“We’ve been promised that you’re going to be put on an evacuation flight.’”

John boarded the DC3 aircraft, intended for transporting records, along with Glen and Bob. The seats were lined with boxes full of records — child histories and medical documentation from the children that had been in their care.

Left Behind in Vietnam

When they arrived in Singapore, their first stop, they called the Holt headquarters immediately.

“We called the office in Eugene to let them know we were out,” John says. “They said that they had just received a call from a Holt staff member in Saigon. How on earth they managed to get a call through — I don’t know. But they were pleading for Holt to get them out.”

As they waited on the airfield for their flight out, the Holt staff were told, “You’ve got to get on the bus. We’re going to have to take you back to the Holt office.”

The staff pleaded, “There are North Vietnamese soldiers coming down the street. Isn’t there anything you can do to help us get out?”

John says that while some of the Holt staff in Vietnam did subsequently get out, others didn’t. “We know what happened to some and others we don’t,” he says.

Between 1975 and 1995, over three million people fled Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. More than 2.5 million refugees resettled around the world. And it is estimated that between 25,000 and 50,000 refugees perished at sea.

Reflecting on This Pivotal Moment in History

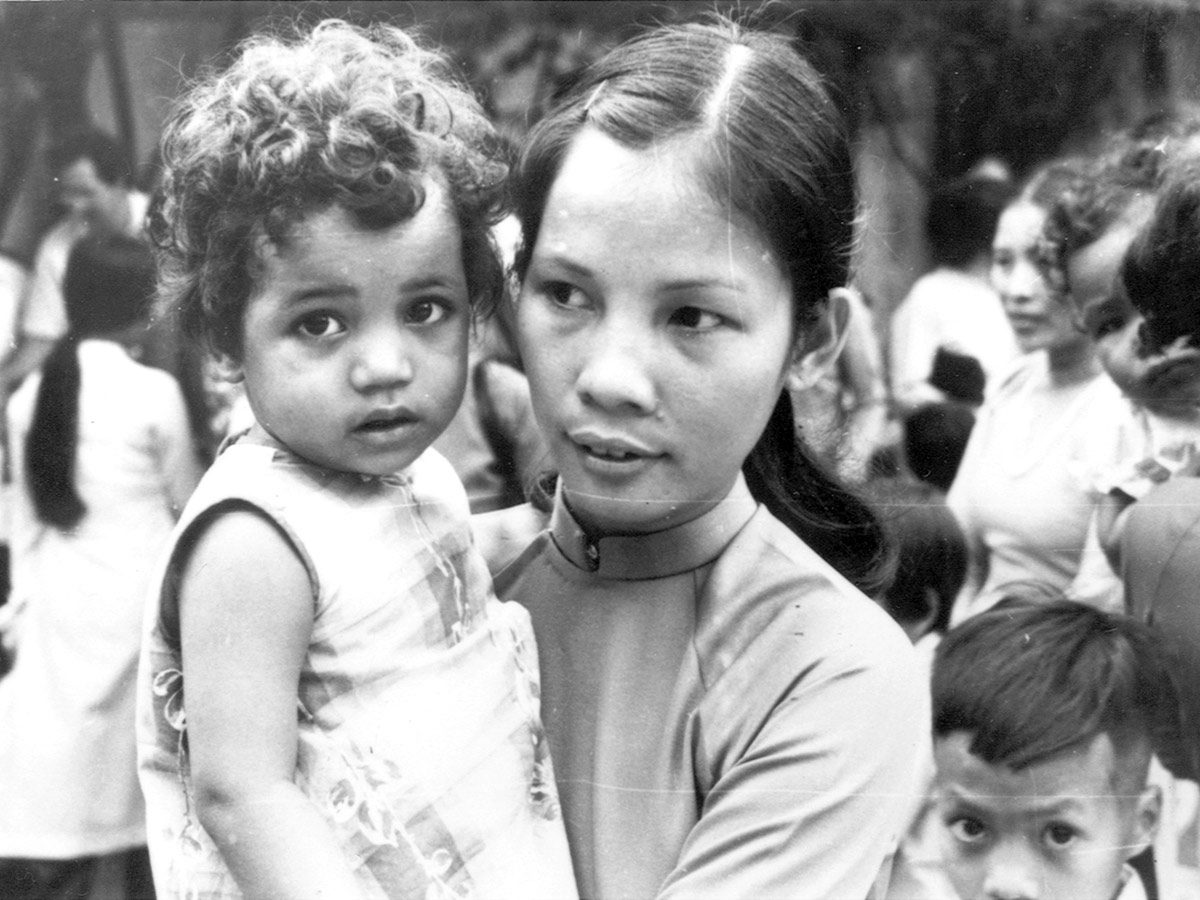

Had it not been for the evacuation of children in Holt’s care, John says their fate may have been grim. Many of them were biracial children born to Vietnamese mothers and foreign soldiers, caught in the grip of poverty with no family to care for them. Much like the children born to Korean mothers and foreign servicemen who Harry Holt felt called to help two decades before, the “Amerasian” children born during the war in Vietnam would likely face discrimination throughout their lives.

“There’s a term that applied not just to Amerasian children but to Vietnamese street children: ‘The dust of life’ or ‘bụi đời.’ If you were a street child without means, you were not treated very well,” John reflects. “A lot had to do with social status — if [they were] on the streets or in an orphanage without the social status of being from a higher society family … I don’t even want to necessarily think about what would have happened to them. By that point, they were already separated from any known birth parent. [They] would have been in very, very, difficult circumstances.”

Their futures were forever altered by the evacuation flights that famously came to be known as Operation Babylift — bringing them across the ocean for a chance at a new life and into the arms of loving adoptive families.

“I don’t know how many people in this day and age know there was something called the ‘babylift’ in Vietnam,” John says. “But the babylift was one moment in time, and it was part of a much, much bigger story about Vietnam. And for that one moment in time, I like to think of it in terms of Holt’s role and how it conducted itself in that moment.”

More Stories to Be Told

John William’s incredible account of the events that transpired in Vietnam is just one story of so many.

The story continues with the lived experiences of adoptees today — what were their childhoods like joining adoptive families in the United States? Where are they now?

Help a Child in Greatest Need

Give emergency help to a child who is hungry, sick or living in dangerous conditions. Your gift will provide the critical food, medical care, safety and more they need when they need it the most.