In Ethiopia, students head to school this month with support from their Holt sponsors and donors — some for the first time.

In the first week of September, the dark mass of stormy skies over Shinshicho finally breaks apart, however briefly.

There is still a 90 percent chance of rain again today, the first day of school, as there has been for nearly three months. Between the thunderstorms, wind and seemingly endless rain, the dirt roads are washed out and muddy, with deep puddles blocking even the most major roadways.

Soon, though, the rainy season will change — returning to a hot and dry dust storm and droughts that make farmers curse their land.

Born sixth in a family with seven children, 9-year-old Tigabu has more than once wondered if, indeed, his family is cursed. His parents are subsistence farmers who struggle to afford even basic necessities, like food or clothing. His four sisters and two brothers help where they can to earn extra income for the family, but that often means skipping class to help their parents harvest or carry crops to market.

Until recently, however, Tigabu and his siblings had no school to miss. Their opportunity to attend school is a new one.

Tigabu was born deaf — a condition he shares with his grandfather and elder brother and sister. In Ethiopia, physical disabilities are heavily stigmatized, and many villagers still believe that only a family curse could cause their children to be born deaf.

“Because deafness and all disabilities, really, are viewed as a family curse, the response is that children are hidden away,” says Dan Lauer, Holt’s vice president of programs in Africa. “They aren’t taken out into the public. Locally, understanding about disabilities in Ethiopia is very behind.”

In Tigabu’s hometown of Shinshicho, however, this so-called “curse” affects many families in the community. In Shinshicho, an abnormally high number of children are born deaf. Some doctors and government officials speculate that malaria or potentially malaria medicine or genetics are to blame, but they have yet to identify a certain cause. And, despite the prevalence of deafness, resources for the deaf — including educational opportunities — are almost non-existent, especially for those who don’t speak sign language. Many deaf children are hidden away, marginalized from the community, excluded from schools, and destined for a life of poverty. To be deaf and poor is an even worse fate, as deaf children living in impoverished families face even greater discrimination. They are powerless, resource-less and socially isolated.

With nowhere to turn and little hope for their children’s future, many families feel compelled to abandon children born deaf — even if they are healthy in every other way.

Tigabu’s parents, however, did not abandon their three deaf children. And today, a stormy, hot day in September, is Tigabu’s first day of 4th grade, and he buzzes around his home with excitement. Tigabu’s father, Amanuel, believes in education and he knows that his children’s best chance at a future free of poverty and instability — a life of subsistence farming — depends on it. He promised himself long ago that he would pursue education for his children at any cost.

For many years, there wasn’t a school in Shinshicho that would welcome his three deaf children. Without resources to learn sign language on his own, even Amanuel was cut off from communicating with his children — and Tigabu grew disconnected and introverted, struggling to express himself emotionally.

Then, in 2009, Holt came to Shinshicho — first renovating a local clinic, and then partnering with the community to build a full maternal-child hospital to serve the region’s nearly 250,000 people. In recent years, Holt also developed programs to strengthen families at risk of separation from their children. Through our work in the community, Holt heard about the need for a school for deaf children and decided to help. A Shinshicho resident donated the land and space, and we worked with the community to determine how we could help.

Although Amanuel’s family lived a two-hours walk from the new school, they showed up on the first day with hope in their hearts.

They weren’t the only ones.

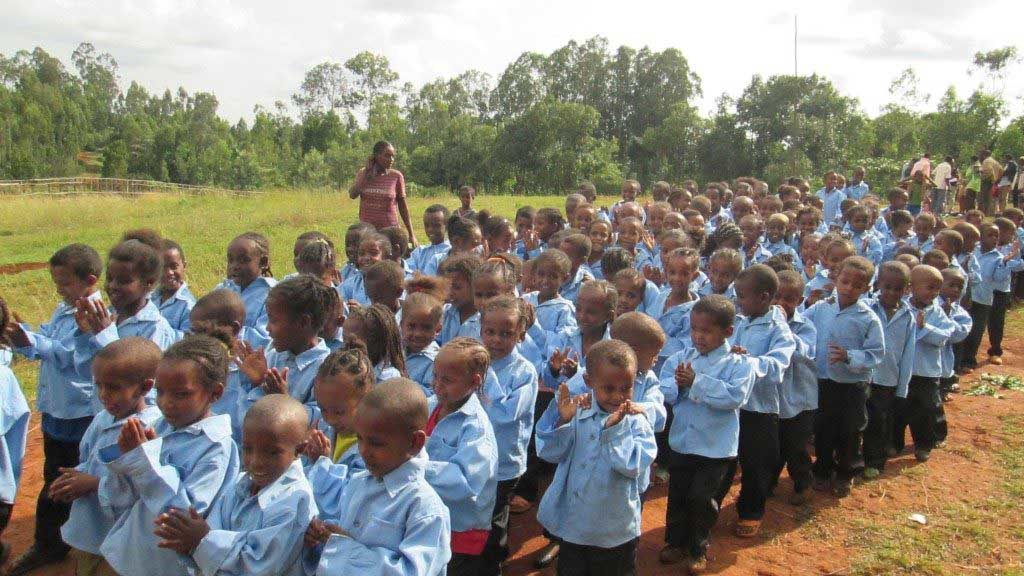

The new school had room for about 50 students, but on the first day more than 200 deaf children arrived — eager to learn.

In the three years since, Holt has helped hire more teachers and expand the school — even adding a free lunch program for the many children who walk miles to attend and show up with empty tummies.

“The school is very liberating for deaf children and their families,” Dan says. “It’s right in the middle of town, so visible to the public and the community. It’s helping to change the way the people view deafness.”

This year, more than 400 deaf children enrolled for classes, many able to attend thanks to Holt sponsors, whose monthly $30 in support provides more than just school fees, uniforms and supplies. The children in Holt’s sponsorship program also have access to medical care, supplemental food and clothing, and vocational training and education for their parents. With Holt’s help, these families will grow strong, stable and self-reliant — eventually generating enough income to cover all their needs and invest in their future.

Today, Amanuel says that Tigabu is confident, healthy and active. He is making great strides in his development, and he is learning to communicate through sign language. Amanuel says he now greets people with excitement, smiles more and shows great enthusiasm for life. On Saturdays, Amanuel joins Tigabu and his siblings at the deaf school, where he is learning to communicate with his children alongside other parents in his community.

As the school has grown and offered more services, it has outgrown its space — but soon, that won’t be a problem. This year, a German nonprofit that heard about the amazing school plans to build a new facility for the current students, but with enough room to grow and welcome more deaf children. After the building is complete, Holt will continue to partner with the school, offering support to families and continuing the free lunch program for students.

Across this region of Ethiopia, most subsistence farmers depend on the yield of their farmland to survive. They sow crops to provide enough food for their families, and if they are lucky, a little additional income.

Farmers pray for adequate weather. Too hot, and there could be a drought that kills their livestock or crops. Too rainy, and flooding or erosion could wash their harvest away. It’s a delicate balance, and one that is completely outside the control of families who rely on agriculture to survive. Especially for adults with little education, farming can be the only source of income available. In hard years, they can literally lose everything and have no safety net to catch them.

That’s why education is so important. It gives children options as they grow into adults — options to choose a different type of career. It’s also why we often partner with schools.

As Dan says, “Staying in school is a key indicator for long-term quality of life in Ethiopia.”

Our approach to child welfare in Ethiopia is similar to our approach in many of the other countries where we work. Through our family strengthening programs, we stabilize or reunite vulnerable families by providing resources to keep children in school, and other key services like nutritional support or emergency food, access to healthcare, and vocational training to help families grow strong and self-reliant long-term.

Holt program staff tailors services to the needs of the community, responding on both an individualized, child-centric basis, as well as working to fill gaps of need in the community — often through education or by providing support to those who have been marginalized due to poverty or special needs.

In Shinshicho, for instance, many HIV-affected families struggle to find resources and support, and many children are at risk of separation from their parents. We target these families, and Holt sponsors help provide medical care, educational assistance, emergency food and opportunities for parents to learn new job skills. This not only helps families grow strong and independent, but builds a network of love, acceptance and support for families experiencing the same hardships.

However, our first prerogative is to keep children in school.

While the challenges of special medical or developmental needs often keep children from school, the biggest and most prevalent roadblock to education is poverty. Poverty is so pervasive in Ethiopia, it is the most common reason for children to drop out. As many children can’t afford school fees, they either quit or attend school so irregularly that they fall far behind. Even for children who can afford the fees, many show up unprepared and quickly lag behind the class or never truly learn core skills, like basic arithmetic or reading and writing.

In the United States, most children attend several years of daycare or preschool before they start mandatory education requirements. With greater availability of programs to help struggling parents afford early education, parents in the U.S. often begin teaching basic things, like numbers and the alphabet, to children well before formal classroom instruction begins. This educational foundation is critical to children’s long-term success in school, and it is something many Ethiopian children miss out on.

“The poverty level of families in Ethiopia means families can’t access the building blocks to prepare their children for school,” Dan says.

Through our work with vulnerable families in Shinshicho, Holt found that many children who start school — even at 5 or 6 years old — weren’t prepared for classes. They lacked an understanding of structure, routine and basic, preschool-appropriate knowledge.

Government-run public schools in Ethiopia are not free, and they typically don’t offer early education like kindergarten.

“Children have to learn how to learn,” Dan says.

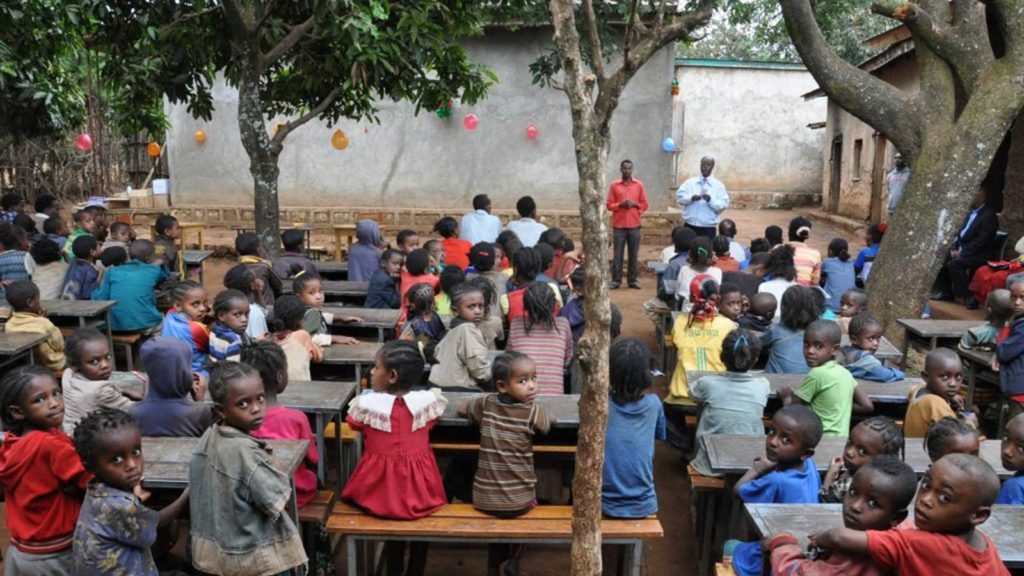

To help children learn how to learn, Holt began partnering with a church in rural Ethiopia, about a 20-minute drive from Shinshicho. In 2010, we provided the funding to build Wallana Kindergarten — a three-room school for children in the community — while the church hired teachers.

“We wanted to provide education to children who were showing up to school and not doing well,” Dan says.

Kindergarten literally means “children’s garden,” and historically, this educational approach combined singing, playing and other childhood activities, like drawing, to introduce children to the joy of learning. A U.S. survey by Harvard economists in 2013 suggested that children who attend kindergarten are more likely to attend college, less likely to become single parents, and have a much higher earning potential over their lifetime.

Kindergarten sows the seeds for patience, discipline, manners and perseverance. It also provides a safe place for young children during the day while their parents work. Truly, kindergarten in Ethiopia is a place to help children grow and bloom into lifelong successful students.

Last year, the kindergarten expected 130 students, but when more than 180 enrolled, the teachers had to act fast to create a plan to include all the students. They decided to split the children into morning and afternoon sessions, which not only meant that every child could participate, but that classroom sizes would be smaller and allow for more individualized attention. Children aged 4-6 are welcome to enroll and attend classes for up to three years, or until they are ready to transition into primary school.

One of those students, 7-year-old Rediet, is returning to Wallana in September for a second chance at an education. Already, he’s dropped out once.

Rediet has one older sibling and three younger siblings. He lives with his mother and father on a small plot of land on a rural hillside outside of Shinshicho. The family lives on subsistence farming, and struggles to provide school fees for their children. When Rediet started school at 5 years old, his father was not pleased with the quality of the education he received. The government-run public school was packed with students, and Rediet’s father could tell his son was not learning. Rediet said he spent most days playing with his neighborhood friends.

Rediet’s father knew that education is crucial for his children, but on the other hand, he couldn’t afford to pay for his son to be in a class where he wasn’t learning.

Rediet dropped out of the public school, and then in January 2014, Rediet’s father enrolled him in Holt’s kindergarten program nearby.

“In Ethiopia, providing education has many challenges,” Dan says. “We are working in poor communities where large families are common, and we are competing against a failed public school system.”

The kindergarten, Dan says, is a community attempt to support kids and families and keep children in school.

Today, after just one semester at Wallana, Rediet is doing much better in school, and he is excited to start his first full year in the program. Already, Rediet has shown improvements in reading and writing, and he has learned to write English, Amharic and Kembatigna letters. He’s learned to write his name, add and subtract two digit numbers, and draw animals.

Holt sponsors also support many of the kindergarteners, so their school fees are usually covered and their family may receive additional support.

As part of the kindergarten program, Holt helped hire a social worker to support families, provide early intervention when necessary, and ensure that vulnerable children and families receive the counseling, resources and support they need. In this way, Holt is helping to keep children in school and prevent child abandonment.

This year, a parent group is also helping to improve the school, adding a fence and a playground. Holt hopes to continue providing support, potentially adding more teachers in the coming year. We’ve also added a kitchen to the school, and with help from the parent group, we will begin providing nutritious snacks and lunch to students — offering an opportunity to teach children and families about hygiene and nutrition, and their impact on health and development.

Already, Rediet’s father has seen such changes in his son. Rediet is confident and speaks with boldness. He is obedient and takes pride in his appearance — he loves new clothes! — and he keeps hens as a new hobby. Now that Rediet attends Wallana Kindergarten, his father is hopeful for what the future holds for his son.

With the educational opportunities Holt is helping to provide in their community, thousands of families in Shinshicho, Ethiopia feel a break in the storm this September. They are sending their children to school — some for the very first time. They are learning that their land isn’t cursed. It’s fertile ground, ready to bloom, ready to provide for them for years to come.

Billie Loewen | Former Holt Team Member

Thank you for this article about your work in Ethiopia. We currently sponsor a little girl there and this gave me more info than your newsletters have. I was trying to Google the languages she speaks and is learning to write. God bless you for your strong work there!!