On January 25, 2018, we said a heartbroken goodbye to Dr. David Hyungbok Kim, who alongside Harry and Bertha Holt pioneered the modern practice of international adoption. He lived 86 extraordinary years.

Earlier this year, as summer turned to fall, Holt leaders and donors came together to create a tribute to our founders in the lobby of our building in Eugene. Along one wall we would hang framed photos of Harry and Bertha Holt above a glass case holding pieces from our history as an organization. Medals and awards, flight logs and newspaper clippings. A copy of the original Holt Bill allowing Harry and Bertha to bring home eight children from Korea. A pair of pink Korean silk shoes that Bertha once wore.

But along one wall — a wall that runs the full length of the room — we would create a mosaic with pictures of children who have come home to families over the years. Pieced together, in shadow and light, these individual photos would capture the image of one person whose legacy is truly bound to every child who has ever came home to a family through international adoption. A person who, with a deep Christian faith, devoted his whole life to advocating for orphaned and homeless children.

Truly, whenever and wherever you see a child in the loving care of a family to which they were not born, you see the beautiful heart and the incredible, enduring legacy of Dr. David Hyungbok Kim.

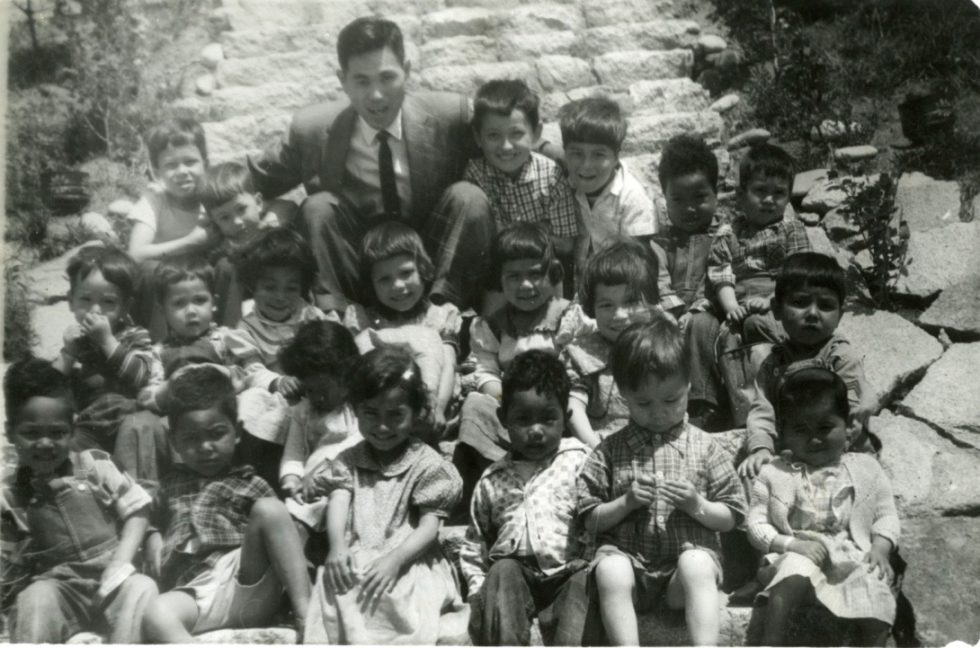

David began his life’s work in the summer of 1956, in South Korea, when Harry Holt hired him as the first employee of the nascent Holt Adoption Program — the program that would become Holt International. With English skills he learned while working for an American Army chaplain during the Korean War, David started his employment as an interpreter for Harry Holt. But the American lumberman soon recognized David’s skills, as well as his dedication to the mission that had called Harry to Korea — to seek families for the thousands of children left orphaned or abandoned in the wake of the Korean War. David quickly rose in Harry’s esteem, and soon, Harry Holt entrusted him to lead the Holt Adoption Program, making David the first Korean to head a U.S. charity. He was just 25 years old.

As head of the Holt Adoption Program, David would go on to oversee the adoption of thousands upon thousands of orphaned and homeless Korean children into loving families in the U.S.

“We had to reinvent the wheel in almost every situation,” David said of the early years of the program, during a 2012 interview with The Korea Society. “National adoptions had never occurred in Korea before, and the legal process for adoption in Korea — especially for American families — was done under a different context. Processing legal papers through the Korean government was extremely difficult.”

David said it wasn’t easy, with government employees often resistant to the mounds of paperwork required to process each adoption. Undeterred, David went from official to official, moving them with his compassion for the children. “I spent a lot of time pleading with them, reminding them that we had all these kids to care for, and they were the only ones who could help,” he said.

As the majority of children who came into care in the mid-to-late 1950s were abandoned — or otherwise without any identifying information — David became their legal guardian, which authorized him to sign immigration and adoption documents on their behalf. David’s wife, Nancy, recalled how one evening when they were newly engaged, he told her that he was the legal guardian to over 2,000 babies to be adopted by American families.

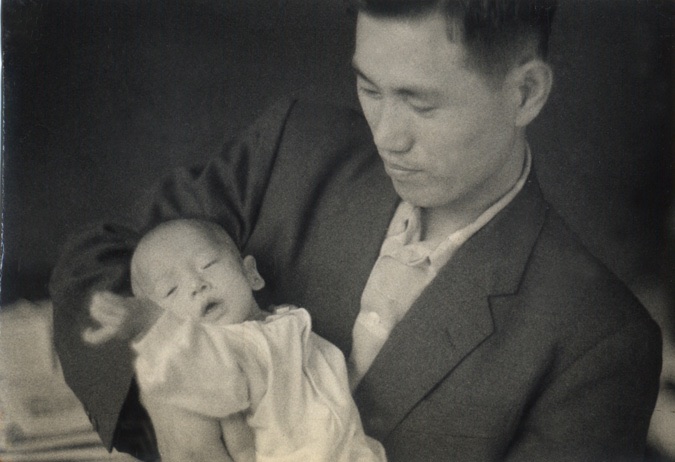

As the children’s “first father,” as he once referred to himself, David also became a parental figure to the children while in care in Korea — viewing his role as more than just a legal title. He tenderly cared for them, changed their diapers, comforted and carried them when they were ill, gave many haircuts, and provided the older children with instruction and guidance.

Later, in his 2001 memoir, “Who Will Answer,” David would share how much he loved visiting them once they were home in their adoptive families. “They were in my heart and soul, having worked with them closely every day at the center,” he wrote.

Many Korean adoptees only briefly carried the “Kim” name, replacing it with the American surname of their adoptive families once home in the U.S. But to David Kim, this name change symbolized the revolution that the Holts began, and that he championed throughout his life — a revolution in the concept, color and composition of family.

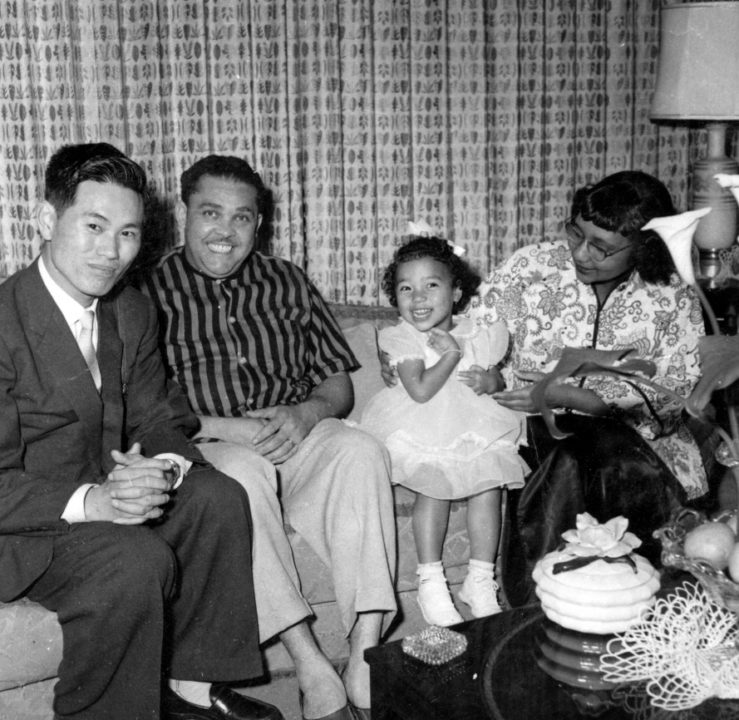

At a time of divisive racial tension and discrimination in the U.S., David demonstrated that love and compassion can transcend race, religion, ethnicity or nationality. “It was the 1950s,” he said in 2012. “And despite that, [Harry Holt] adopted children from Korea. He brought Korean children back into the United States to become part of American families. Until then, adopting black children, Hispanic children or Asian-minority children was almost completely unknown.”

While changing attitudes in the West, David and the Holts’ work also began to change hearts and minds in other countries — including Korea. It wasn’t until 1976, when the Korean government passed new adoption legislation, that children adopted domestically in Korea could take on the new last name of their families. Before then, David said, most adoptions were done to help perpetuate the family name — and for that reason, most families only adopted boys. But “our presence changed our country’s thinking,” he said of the Holt Adoption Program.

“The Korean government saw that once they put their seals on documents for children to come to the United States, we did not discriminate in terms of which child went to which family,” he said. “It was based on meeting the needs of the child. It was child-centered adoption. We did not care whether a ‘Kim’ was adopted into the Smith family or the Gonzalez family or the Jones family.”

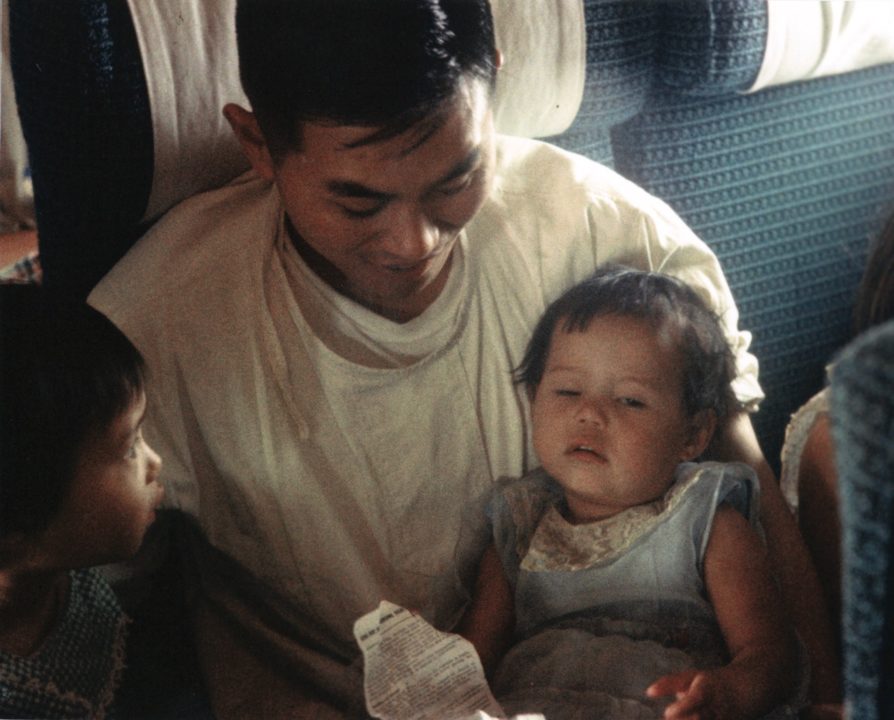

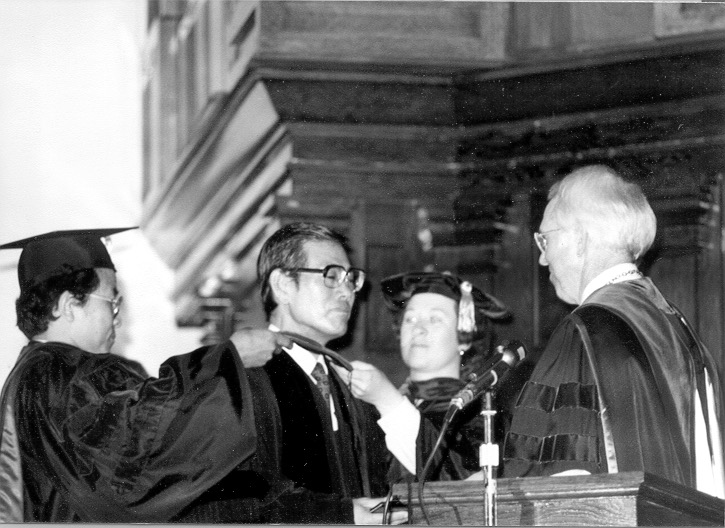

During his time overseeing the Holt Adoption Program in Korea, David personally escorted hundreds of children by chartered flight to their adoptive families in the U.S. With almost 60-100 children to a plane, and with little or no rest, he fed and comforted the children. He often joked about the number of diapers he changed on what was then a more than 40-hour journey from Seoul to Portland, Oregon. And in 1982, when he received an honorary doctorate of divinity from Northwest Christian College, he playfully described it as a “D.D. — a doctor of divinity and diapers.”

But in the chaos and poverty following the war, David also endured harrowing experiences that would stay with him forever.

“Unfortunately, one child was already very ill by the time the paperwork was completed,” David said in 2012, of one early flight from Korea. “I had that baby on my lap and was using a portable oxygen mask to help the child keep breathing. And my gosh, I don’t know. My arm was numb, and I wasn’t feeling anything at that point. With all that, the baby succumbed. Nothing like that had ever happened to me before … It was a devastating experience.”

Other children who came into care after the war didn’t survive long enough to make the flight to a family in the U.S. “A lot of children arrived malnourished,” he said in 2012. “They were all skin and bones … The skin was literally wrapped around the bone.”

The suffering of children that David witnessed during his early days working for Harry Holt in post-war Korea in many ways shaped the course of his life and career. But long before he met Harry Holt, David and his family endured incredible suffering of their own.

Born in 1931 in Longjing, Manchuria — a region that is today a part of northeast China — David described his childhood before WWII as idyllic.

“The second child and first son of a Presbyterian minister, my life had been filled with simple country activities,” he wrote in “Who Will Answer.” “My family owned farmland upon which several families grew rice for a share of the crop. My siblings were an older sister, three younger sisters and a younger brother, and we enjoyed a comfortable existence with virtually no cares.”

By heritage Korean, David’s family emigrated to Manchuria from northern Korea in the early twentieth century. Sent by the Canadian Presbytery to spread Christianity, his grandfather was the region’s first Christian missionary from Korea.

But a year before David was born, Japan occupied Manchuria, and David and his family were stripped of their Korean identity. Because his grandfather worked with Canadian missionaries, his family was under constant surveillance by the Japanese military police, who suspected they were spies.

“Once the war with the Japanese ended, the Russians arrived, bringing with them a different type of oppression and yet another nightmare,” David said in 2012. “My family had many ups and downs during these years and we faced a lot of hardship. I believe my patience and desire to persevere were developed during these years, and these many difficulties taught us how to survive, regardless of the conditions around us.”

Russian domination gave way to the Cultural Revolution in China, during which David’s family experienced religious persecution — and David watched his father be put on trial as an intellectual, the first minister to be charged.

While many other intellectuals were publicly stoned to death during the “people’s trials,” David’s father was miraculously released. Shortly afterward, with the threat of imprisonment and death still looming, David escaped with his father to South Korea, and three months later, his family joined them in Seoul.

“My memories of that day are so vivid. It was March 17, and the Tumen River was still frozen,” David said of the day he escaped to Korea. “Walking on the frozen ice, we made it south, and dad asked me to kneel. We both prayed in thanks for our lives, and 40 days later our family members arrived.”

Their respite, however, was short lived, with the start of the Korean War in 1950. During the war, his father was imprisoned by the Communists because of his faith. His father succumbed to the injuries he suffered, and suddenly David became the head of the household, the sole support for his mother and five younger siblings. He worked any job that he could find, while at the same time studying for the college entrance exam. Determined to ensure a better future for his siblings, he worked tirelessly to put all five of his siblings through school, including college. David was accepted into Seoul National University, the most prestigious in Korea, and in 1959, he received his degree from the Teacher’s College.

From 1956 to 1963, David remained in Korea, leading the Holt Adoption Program. Throughout these early years, working side by side, David and Harry Holt developed a bond so profound that David later described it as “almost a son and father relationship.”

“We had an understanding, and we both thought the same way,” David said in 2012. “That’s what helped us be so successful and accomplish as much as we did.”

One conversation that David shared with Harry Holt early in Korea had a particularly strong impact on him. The title of David’s memoir, “Who Will Answer,” is also drawn from this moment — from a question that Harry Holt posed to David while they stood, praying over the freshly dug graves of children who did not survive.

“After the prayer, Mr. Holt looked me straight in eye, and asked, ‘Brother Kim, who will answer for these children when we stand before God?’” David wrote in his memoir. “Silence prevailed as we searched for an answer. After a few minutes Elder Lee and I shoveled frozen dirt onto the little coffin. There were no words from any of us, even after we arrived back at the center. The question stayed in my thoughts for the next several days. What would be my answer when I stood before God? It made me think of the responsibility that I bore for every baby who died under our care.”

David carried this responsibility long after Harry Holt passed away, and he continued to reflect on this moment throughout his life. In June 2016, during a speech David gave at a reunion of the “first wave” of Korean adoptees — adoptees who came home during the mid to late 1950s — he again shared this memory.

“You know, those words stood out until today,” David said, now no longer a young man just starting his life, but a man in his mid 80s, reflecting upon how he had lived.

“I was very lucky,” he told the audience of Korean adoptees, themselves in their late 50s and early 60s. “There was a reason for me to be there when he spoke. I keep thinking about that. He said, ‘Who will answer,’ then later said, ‘when we stand before God?’ He was really burdened for the Korean children. You think about this. It’s not a simple statement. I hope that anybody who works with the kids will think about this all the time. And his words made me go all this time.”

While still in Korea, in the 1960s, David created one of his most significant legacies — pioneering foster care for children as a more nurturing alternative to institutional care. The foster care model that David built in Korea would later be recognized by UNICEF as best practice for children in care, and would go on to be studied and replicated throughout the world.

During this time, he also strived to ensure that the children not adopted, because of disability or for whatever reason, would not be forgotten and turned away. He searched for three years to find a suitable site on which to build a permanent home for these children. He found the site at Ilsan, which remains today a community, home and family to hundreds of disabled residents, some of whom have lived there for their entire lives.

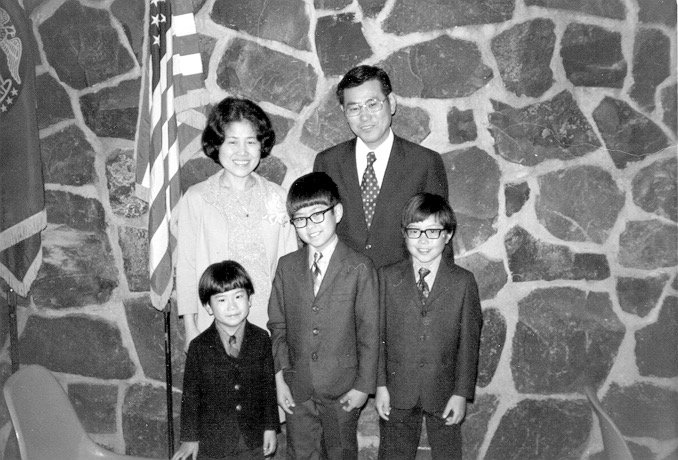

It was in those years that David met his wife, Nancy, in Seoul, and in 1960 they married. Two sons, Paul Sungbae and John Hyunbae, followed. Their third son, Andrew Inbae, was born in Eugene, Oregon. As they built their own family, David continued to work tirelessly to bring homeless children into loving families through adoption. David and Nancy would open their home to older adoptees who were having difficulties in their initial adoption placement, refusing to send them back to Korea, and cared for them alongside their own children until a permanent adoptive family could be found.

As the Holt Adoption Program grew, so did David’s recognition that to successfully lead this international organization, he needed to acquire professional knowledge. He applied to the Master of Social Work program at Portland State University, and in 1963 was accepted with a full scholarship. David traveled alone to the United States first, and supported himself by working as a gardener. Once he became more established, he brought his wife and two young children.

In April 1964, while David was studying in the United States, Harry Holt died of a sudden heart attack in Korea — leaving the future of the Holt Adoption Program in doubt. David was torn, and was prepared to return to Korea to carry on Harry’s work. But after meeting with Harry’s wife, Bertha, and brother Phillip, David decided that he should stay and complete his education for the future of the organization. In 1965, he earned a master’s degree in social work from Portland State University, and thereafter was hired by Holt as Associate Director.

In the years that followed, David worked alongside Bertha Holt to mature the Holt Adoption Program into Holt International, the world’s leading global child welfare, family preservation and adoption organization. He played a central role in expanding Holt’s work to many countries around the world, including Vietnam, India, Thailand, China, the Philippines, Mongolia and North Korea.

From 1980 to 1990, David served as Executive Director of Holt International, and after his retirement he continued to serve as President Emeritus and lifetime member of the Holt Board of Directors. He remained active with the organization, serving as an ambassador at large, an advocate for children, a fundraiser and a mentor.

Throughout his life, he always made time to listen to adoptees and adoptive families, and from his conversations with them, realized that there was a great need within this community for answers to questions that arose in their lives, concerning their birth heritage. To address this need, he designed the first Motherland Tours to Korea for Korean adoptees, and in 1975 led the very first tour. He personally led all of the tours for many years, and established a fundamental change in social work practice. Today, many other organizations and agencies offer similar programs, enabling thousands of adoptees and adoptive families to benefit from his insight.

Seeing how successful Holt motherland tours became, he also saw a need among younger adoptees in developing a sense of self and pride in their birth heritage. To that end, he established Holt Heritage Camp. As most early Holt adoptees were from Korea, the majority of Holt’s first camp participants were also of Korean heritage. But today, hundreds of adoptees from countries across the world, including the U.S., attend what is now known as “Holt Adoptee Camp” every summer.

David helped to establish social work as a practice in many developing countries, built bridges and understanding between cultures, and helped cultivate Holt’s child-centered model of practice that prioritizes keeping children with their birth families, whenever possible. He developed foster care, pregnancy counseling and family crisis counseling programs, domestic adoption and other services in the U.S. and many other countries. In 1968, he helped created an unprecedented movement to adopt older children and children with special needs.

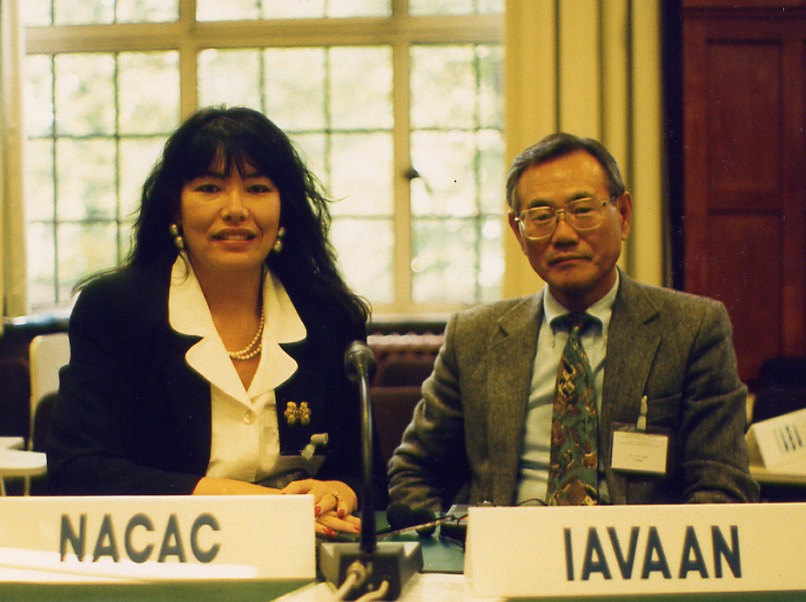

And when nations gathered in the early 1990s to draft The Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption, David stood up to fiercely defend every child’s right to a family, and to advocate for long-term, post-adoption services. His impassioned eloquence resulted in a preamble that clearly states that children need parents of their own, and that adoption is the best solution for children who cannot remain with their birth families.

Holt’s vice president of policy and external affairs, Susan Soonkeum Cox, sat alongside David as members of the U.S. delegation to The Hague. The first adoptee appointed to Holt’s board of directors, Susan worked for many years alongside David, a man she described as an “incredible human being.”

“I had the benefit of being at The Hague with David,” Susan shared during a 2017 Holt staff meeting honoring David. “Since The Hague is so much a part of everything we do now, I wish that everyone here could have seen David really stand up and fight, truly, for the long-term post-adoption [services] for kids. There were law professors. But David could speak from the benefit of being a social worker and being able to speak in first-person, and the impact that he had on persuading 66 countries was really amazing.”

With a legacy beyond measure, David’s life continues to inspire people around the world who work to ensure stable, loving families for children. This is especially true at Holt.

“He taught me so much about care and passion, and compassion for ‘the least of these,’” Holt’s president and CEO, Phil Littleton, says, describing David as his “personal hero and mentor.”

David’s eldest son, Paul, also carries on his father’s legacy as Holt’s director of Korea and Mongolia programs. “He was always self-sacrificing,” Paul says. “Any penny that the organization received, he always felt that it should be used for the children and nothing else. Whenever he traveled overseas, instead of staying in a fancy hotel, he would stay at a guesthouse at the orphanage he was visiting, at the YMCA, in very, very humble quarters. Sometimes in places like India, when he was staying at a guesthouse in the orphanage, he would tell me about being able to see the stars in the cracks of the beams overhead … He truly believed that we are stewards of the gifts we received and that we are privileged and entrusted by God to fulfill this mission.”

Paul described his father as a “very faithful and humble servant,” and someone whose compassion and love and faith made you want to “work just that much harder and to be a better person.” He also described him as “just a wonderful dad” who always put his family first.

After observing her young husband care for 97 babies over 48 hours on their first flight together from Seoul to Portland, Oregon, David’s wife, Nancy, began to realize that the man she married was “not just an ordinary man, but chosen by Harry Holt as his partner in Christ.”

“His devotion and commitment to saving little lives inspired me deeply,” she said of her husband.

During his lifetime, David was honored by universities, international organizations and the governments of many nations. Most notably, he was an honoree and recipient of the 2001 Kellogg’s Humanitarian Award. And in 2005, he received the Civil Order of Merit by the Government of the Republic of Korea, the highest civilian award that can be conferred by the Korean government.

But for David Kim, the greatest honor of his life was seeing the outcome of all that he had worked for — of meeting adoptees, now grown, and with families, lives and achievements of their own.

“My biggest thrill since I was retired from Holt was seeing the adult adoptees gathering in Washington D.C.,” David said during a Holt interview in 2014. “And it was really heart-moving. I was so happy! I often wondered if what I’d done was the right thing or not. How they fared, kids I’d placed in homes in the United States. And I’d often wondered how they turned out. But I was very happy to see all those children, came there, celebrating their lives — a successful life, and a happy life.”

During his final speech before the Holt International staff in Eugene, in September 2017, David offered a reminder.

“We’re all torchbearers — the torch that was lit 67 years ago,” he said. “Don’t forget, we’re not creating this. We’re just a torch that was lit by Harry Holt, and we carry that. We have to carry that successfully without having it extinguish. That is, try to find homes for these homeless children. That’s what Harry’s heart was set on, finding homes for the homeless children.”

David Kim is survived by his wife Nancy; his three sons, Paul Sungbae Kim (Beth Keech), John Hyunbae (Julie) Kim, and Andrew Inbae Kim (Catt Rosa); his six grandchildren, Maya, Jonah, Christopher, Naomi, Elijah and Soraya; and the thousands of adopted children whose lives he so profoundly touched.

A celebration of David’s life will take place at the Faith Center on February 24, from 2:00 PM to 4:00 PM. In lieu of flowers, the family has requested that if would like to make a donation in David’s honor, you can give here. Your gift will be used to help children with urgent needs that might otherwise go unmet.

Copies of David’s memoir, “Who Will Answer,” are available for $25. Contact Masha Ma at [email protected] or at 541-687-2202, ext 193 to order a copy.

View David’s 2012 interview with The Korea Society: