Life can be harsh for migrant families in Bengaluru, India. But for 330 young children and their families, this Holt-supported daycare brings education, development, community and hope.

Three-year-old Dipika walks through the door, clutching her mother’s hand. After getting signed in, she walks wide-eyed down the hall where her mom gives her a hug before dropping her off in the classroom. Within seconds, Dipika’s eyes brim over with tears, joining a roomful of other bawling 3-year-olds.

This sound coming from the 3- and 4-year-old room is in sharp contrast to the colorful walls, toys and smiling staff throughout this building.

It’s the first day of the first week of daycare. So while the older kids bound back to their classrooms with familiarity and excitement, this isn’t the case with these youngest ones. Their teachers try to console and distract them with toys, songs and comforting words, but it isn’t doing much. Because when you’re 3 and it’s one of your first times ever away from your mom, daycare is new, unknown and scary.

But here in Bengaluru, India — even right here at the Vathsalya Charitable Trust (VCT) daycare — the children aren’t the only ones who feel this way. Many of the parents are scared, too.

“When I first came to Bengaluru,” says Ana Kria, “I didn’t go out anywhere for two years.” The mother of two boys, 7 and 5, who attend the daycare, Ana Kria and her family used to live in Veru, a smaller town in the neighboring province.

“Everything was new for me,” she says about moving to this city of over 12 million people. “The language was new, the people were new, the environment was new… I was afraid to go out.”

She is not alone in feeling this way. Over 139 million people in India today are considered internal migrants. These are families like Ana Kria’s, who leave rural poverty and move to the city in hopes of finding work and a better life. But when they get here — whether it’s Mumbai or Delhi or in this southern city of Bengaluru — migrant families rarely find what they hoped for. Today, millions and millions of migrants are still stuck in poverty — only now in an overcrowded and overwhelming urban setting.

Not only is moving to Bengaluru scary because of its newness and unfamiliarity, but because it can be hard to survive here. And when families fight for survival, families are in danger of breaking down.

Not only is moving to Bengaluru scary because of its newness and unfamiliarity, but because it can be hard to survive here. And when families fight for survival, families are in danger of breaking down.

The single earner in her family, Sandia works as a house maid and provides for her four daughters, as well as her aging mother. Her husband doesn’t live with them anymore — he went back to their village. When Sandia’s third pregnancy brought her twin girls, making them a family with four daughters, he deserted them. He wanted sons, not daughters.

Her husband wanted to place their twin daughters into an institution, to relinquish their parental rights. But Sandia refused. Although, with her small income, she saw few other options.

Just like Sandia and her family, many migrant families face harsh, heartbreaking circumstances like these.

Most of them live in impoverished slum communities in one-room, often dirt-floored homes. Most of the mothers work as cooks or maids in wealthier families’ homes. Fathers work as rickshaw drivers or construction workers.

“Most parents are illiterate here,” says Hepzibah Sharmila, the executive director of VCT. “And about one percent of the parents know English.” Without knowing English — which has become the language of higher education, Indian media and production, and a prerequisite for nearly all high-paying jobs — and certainly without knowing how to read and write in any language at all, they have few job options. Certainly none that pay well. So while parents, particularly mothers, work exceptionally hard to provide for their children, they have little to show for it.

Any money they do make goes toward their family’s most basic needs — things like food, shelter and clothing. Within the context of survival, preschool or daycare is seen as a luxury. It’s simply not an option for most migrant families. But for working parents, daycare is anything but a luxury. It’s a necessity.

When children don’t go to daycare, they either stay home alone — where they are vulnerable to abusive neighbors and dangers of all kinds — or they go to work with their parents. But this can be dangerous too. Often, these children end up “helping” their parents with their work — essentially becoming free child labor for their parents’ employers.

For some families in Bengaluru, however, there is now a third option… An option made possible by child sponsors.

The Migrant Families’ Daycare

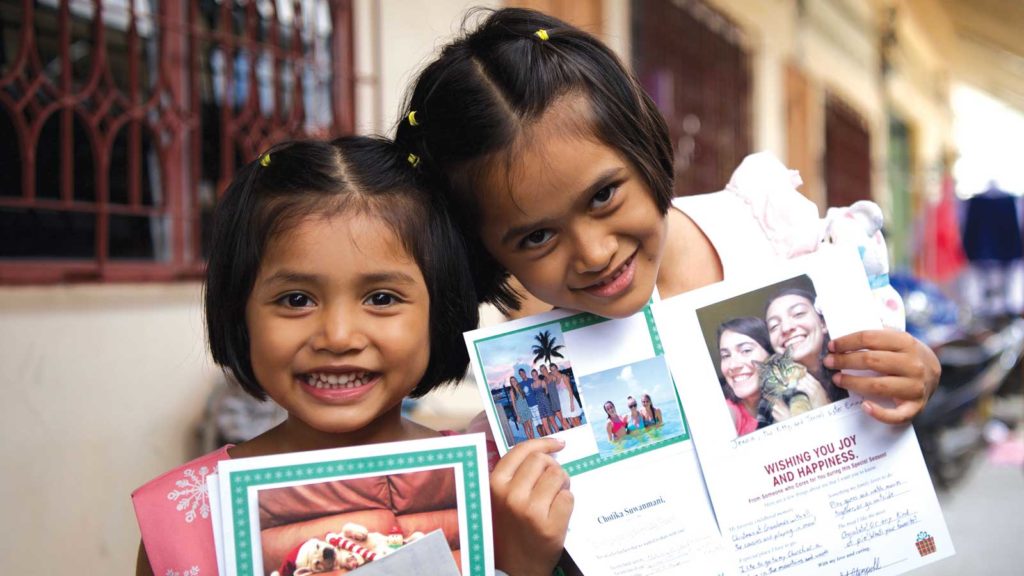

In a four-story building in the middle of several impoverished neighborhoods of migrant families, 330 children are being dropped off for the day. Although the VCT daycare is the only option most families have, it is as high quality as the most expensive of daycares in the city, perhaps even better. Each child at this school has a Holt sponsor.

Some walls are painted with a full underwater scene of brightly colored fish. In classrooms for the older children, posters promote empathy and being kind to one another. As they drop their children off, parents smile and thank the staff before they head off to work.

As children settle into their classrooms, their teachers greet each one by name and with a smile. One class starts off with a song in English about fruits and vegetables; the 4- and 5-year-olds practice threading a shoelace through a wooden board; in the youngest classroom, the kids sit on a mat and follow their teacher’s instructions to jump, raise their hands up and dance to the music that’s playing.

“We hope to give one-on-one attention to each child,” says Sharmila. “We feel that every child should be the focus. [They learn] education, health and hygiene. They should always feel like it’s a family here.”

And part of being like an extended family to each child means meeting their most critical needs. For most children here, their most critical need is for food.

They Come to School Hungry

At mid-morning, the children file down into the lower level of the building – one large room where the children patiently sit in uneven lines on large rugs on the floor. It’s snack time! This morning, their snack is roasted nuts — warm, and full of the protein they need to make it through the day. A couple hours later it’s time for lunch. Today, it’s a hardboiled egg with rice and vegetables.

“We make sure to give them all the food they need for the day while they’re here,” says Sharmila, “because they might not be eating anything else at home.”

“We make sure to give them all the food they need for the day while they’re here, because they might not be eating anything else at home.”

Hepzibah Sharmila, executive director of Vathsalya Charitable Trust

Many migrant children subsist only on the leftovers that their parents bring back from the homes of their wealthy employers. Each day brings the question of whether or not they will eat. As they drop off their children, parents — with tears in their eyes — share this heartbreaking need.

“When I came [to VCT] with the twins, they were underweight and malnourished,” Sandia says about her twin daughters, who first came here at 2 months old. “Because of VCT and the nutritious food they get here, they have gained much weight.”

And because VCT helped meet this basic need for food, Sandia had hope of successfully parenting her four daughters, even without the support and income of her husband.

“But without VCT,” she says, “I would have given my children to an institution.”

Early Childhood Education in Bengaluru

While VCT operates as a daycare, it is so much more than a childcare center. In function, it’s more like a preschool, or informal elementary school.

There’s the pre-nursery class for 3- and 4-year-olds, kindergarten for 4- and 5-year-olds, upper kindergarten for 5- and 6-year-olds and a special informal school for older children who are very behind academically, learning the local language and trying to catch up with their peers.

Walking through the building, children are spoken to in English, they sing songs in English and seem to have a good understanding of it. In Bengaluru, this skill alone is one that will set them up for success in the future. It’s a skill that almost none of their parents have. But it’s one that they have come to value.

At her moment of greatest crisis, when her husband left their family and moved back to the village, Sandia considered moving back, too, with her four daughters. Maybe in the village, she thought, they could all remain together. But she decided against it. Because there, she says, people don’t value education for girls.

“In the village, they don’t give much importance to education,” she says. “So when girls are 15 or 16, they give you off in marriage. I don’t want that. I want my girls to be educated so they can stand on their own feet.”

In the village, they don’t give much importance to education. So when girls are 15 or 16, they give you off in marriage. I don’t want that. I want my girls to be educated so they can stand on their own feet.”

Sandia, a mother of four daughters

Because of VCT, Sandia’s children not only remain together as a family, but their extended family here at VCT makes sure that each of them has the strong early-education foundation they need to thrive.

At VCT, families unite through this common thread — a great desire to see their children educated.

Sundr is a construction worker and the father of four daughters, three of whom are old enough to attend VCT.

“Here, the girls learn to write the alphabet, they learn to speak words in English, they’re singing songs,” he says. “I could not have dreamed of paying for their education somewhere else because it is very expensive. If VCT were not here, I would have kept my kids at home.”

But instead, they are here — learning, playing, developing and already being empowered for a successful future.

And the learning at VCT goes beyond academics. Children also learn about health and hygiene, things like eating more fruits and vegetables, and the importance of bathing regularly. They develop through drama, music, dance, art and physical exercise — all things they would never have the chance to learn elsewhere.

“Because he comes to VCT, he is learning and developing so much,” Ana Kria, who was once afraid of living in Bengaluru, says about her youngest son.

“I am very inspired by looking at him,” she continues. “The way he speaks, the way he behaves — all of that he has learned from VCT. Now, I am learning from my younger son. Every day he wants to take a bath and keep himself clean. He wants to speak very neat and clear sentences. Even if I make a mistake, he teaches me!”

But the children aren’t the only ones who are learning. The parents are learning, too.

Hope for Migrant Families in India

“Once you set your mind to learn,” says Sharmila, “surely all of us can learn.” This philosophy drives her in her work with children at the center, as well as their parents.

VCT facilitates peer support groups for mothers of children in the daycare. These groups are safe spaces where they can encourage each other and share about their lives and difficulties. Through the support of sponsors and donors, many of them have also begun income-generating projects through VCT — small businesses where through sewing or operating a small store or even becoming a driver they can earn a steady income to support their children.

For families who migrate to Bengaluru, life can become suddenly harsh and hopeless. Maybe they feel afraid — not too unlike children in VCT’s pre-nursery class, who find themselves in a new place and seemingly alone for the first time.

But they are not alone.

After several minutes, the 3- and 4-year-olds calm down, and begin enjoying the fun toys, music and other children around them. They begin to learn. This is the beginning of an education that will serve them for a lifetime. Because they are here, they get to play, dance, sing, jump, learn and develop. Because they are here, there is hope that they will continue to go to school, find autonomy in their lives and someday overcome poverty once and for all.

And maybe the same can happen for their families.

Over time and with the support of sponsors and donors, opportunity to grow, and an encouraging community, fear can lend way to hope.

“I feel very happy now,” says Ana Kria, “VCT is a gift for me.”

Become a Child Sponsor

Connect with a child. Provide for their needs. Share your heart for $43 per month.