One by one, family by family, sponsors have over the past 40 years helped to create dramatic change in the lives of children living in some of India’s worst slum neighborhoods. And now, for the first time, children from the slums are beginning to dream well beyond their circumstances.

People are everywhere. Women scrubbing clothes in sudsy buckets with small children strapped to their backs. Grandmothers shelling tamarind pods. Neighbors talking and laughing. Children running, napping, playing, crying, smiling. Bright blue metal siding. Colorful saris and shirts strung high up to dry in alleyways.

It is vibrant — beautiful, even — but a slum community is a hard place to live. Especially for a child. Crumbly concrete. Low-hanging wires and clotheslines. Puddles. Shaky metal staircases. Cramped living spaces with dirt floors. Communal water spickets. Shared toilets. Garbage and dirty wash water pooling in the streets.

And that’s just what you can see.

Alcoholism, domestic violence and lack of education are heartbreaking realities that pervade nearly all of the countries where Holt works. They are the symptoms of desolation. Of hopelessness. And this is all too evident in India.

Some children in this community live with both of their parents, but many live with just their mom or grandparents. And if they do live with their dad, he may drink too much and too often, he may hit their mother — and maybe even them as well.

“The homes have changed slightly from what they used to be,” says Roxana Kalyanvala, the executive director of Holt’s longtime partner organization in Pune, Bharatiya Semaj Seva Kendra (BSSK). She remembers how 27 years ago, when Holt and BSSK first started working in this neighborhood, circumstances were even worse.

Although, being here, it’s hard to imagine “worse.”

We round the corner and see 2-yearold Rohit, wearing the same smudged Mickey Mouse shirt he wore yesterday.

His father, Raju, meets us outside their home, and welcomes us to step inside. It’s dark, and the entire home has barely enough room for four adults to stand in; they nearly touch each other’s arms. Raju points to bedrolls stashed under a makeshift stove, folded neatly on the hard dirt floor. Then he motions outside, where he sleeps, he says, so his wife and two children have enough room to lie down inside.

In a neighboring home, Shraddha tends to her two young sons, who are sick. The youngest is napping in a makeshift hammock made of a scarf that is twisted and tied onto beams of the house. Shraddha can’t read, so she hands over the pill bottle, asking how much medicine she should give her sons.

It’s clear — the need here is still overwhelming. But despite all this, Holt sponsors bring hope.

Sitting smack in the middle of this neighborhood is a one-room, donor-supported community center. It is called the DEESHA — an acronym that stands for Development of Education Environment Social Health Awareness. But in Marathi, deesha means “direction.” This double meaning is significant.

The bottom floor of the DEESHA is one large, bright, open room, and it is in constant bustle with mothers and children of all ages. Children and teens gather here regularly for lessons after school, to check in with their BSSK social worker, and for special, age-appropriate sessions where they discuss healthy relationships, ending domestic violence, escaping child marriage and more. Their mothers come here for nutrition, hygiene and parenting trainings where they learn about the importance of feeding their children a diverse diet that includes more fruits and vegetables, or why their children should wash their bare feet before stepping into their homes.

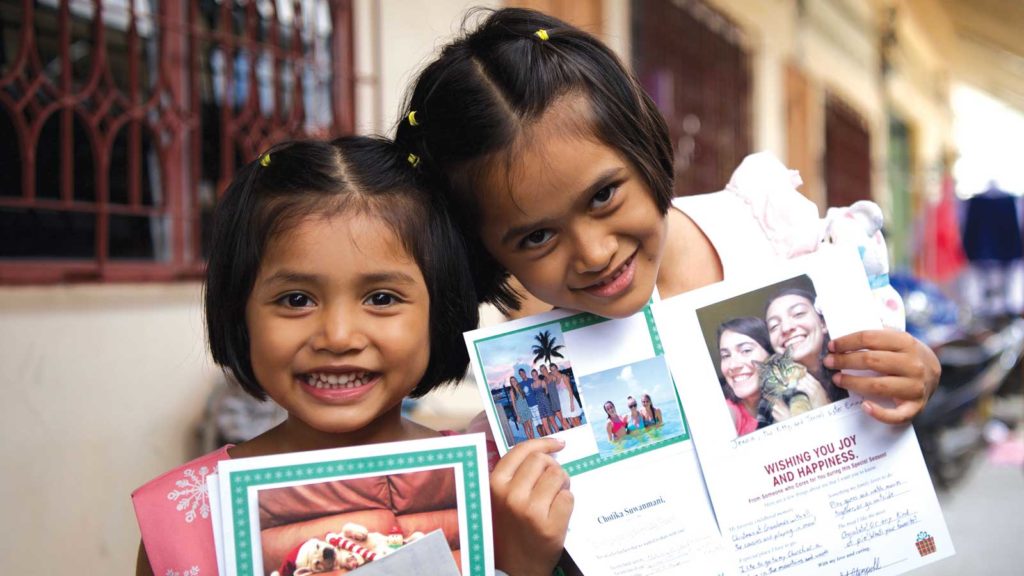

This afternoon, about 20 school-aged children sit cross-legged on the rug — eagerly waiting to answer questions about themselves, answers that we can then share with their sponsors in the U.S.

What do you want to be when you grow up?

Learn more about Holt’s work in India!

See how sponsors and donors create a brighter, more hopeful future for children and families in India!

“I want to be an engineer!” says 9-yearold Arjun, standing up in his green jacket and orange shorts to give his answer.

Ajay, in bright yellow pants and a plaid shirt, says he wants to be an artist.

Each child sitting on the rug gives his or her answer, as others wait patiently to share.

Ten want to be police officers, three engineers, one a teacher, two bodyguards and two doctors. Some say they still aren’t sure.

Vaishali Vahikar, the director of sponsorship at BSSK who also oversees the DEESHA, smiles at each child, encouraging each answer. These answers seem typical – typical answers for children who are living in any circumstance, in any part of the world.

But really, their answers show incredible progress.

Most of these children’s mothers work as “domestic workers” — a title used to describe someone who cooks, cleans or watches children for another family. Most fathers are construction workers, drivers or daily laborers — doing hard manual work that’s often unreliable, pays little, and changes day to day.

“But today,” Roxana says, “you see young ones who want to get into IT, or who want to do computer education, or girls who are doing nursing or teaching. The children have capacities, they have dreams, and they want to do more in terms of education.”

But this didn’t just happen. Change like this takes time, it requires social education and openness to change, and it starts with the parents.

Not only are there 20 sponsored children here, but their mothers are here, too. They also come to the DEESHA to learn.

When the children are done sharing and get up to go play, the mothers take their place, cross-legged, on the same rug. Some hold or nurse young children in their lap.

Vaishali pulls down a map of the world at the back of the room, and directs the women to look at it.

“Here is India,” she says, pointing at their own country on the map, “and here is the United States, where Holt sponsors live.” The mothers all nod in understanding.

Forty years ago, when Holt and BSSK began working in the slum communities surrounding the DEESHA, very few parents were literate — and women especially had very little education. The problem was generational, and cyclical. For parents who missed out on an education themselves, sending their own children to school wasn’t important — they didn’t understand the value, especially when it is so costly. Even if a family did desire to send their children to school, many would send their sons over sending their daughters — doing everything they could to educate their sons, but making their daughters drop out early to get married or begin working.

But family by family, child by child, BSSK social workers began advocating for education. That it is necessary for both girls and boys. That it pays off. That it is each child and family’s best chance for overcoming poverty.

At first, sponsors supported only a handful of children whose parents were open to their education. Today, these children are successful adults. Some work at the DEESHA. Others have become nurses, teachers or technicians. Countless have moved out of the slums, have healthy marriages and are raising their own children now. And because they now understand the importance of education, they are sending their sons and daughters to school.

Slowly, minds and hearts began to change. Parents began to understand the value of an education. More and more children enrolled in the sponsorship program. Today, about 950 children are sponsored in communities like this in Pune — children who are in school, and dreaming of their futures. Positive change is happening, and family by family they are moving out of the slums.

They are moving in a better direction.

But there’s another factor at play in the slum communities surrounding the DEESHA. The families that live here now are different than the ones BSSK worked with 40 years ago. The families who need help today are migrants. Over 139 million people in India are considered internal migrants — parents and their children who leave rural poverty and move to the city in hopes of finding work and a better life. But when they get here — whether Mumbai or Delhi or here in Pune — these migrant families rarely find what they hoped for. Today, millions and millions of migrants are still stuck in poverty — only now in an urban setting.

With each new family that moves to the city, BSSK social workers begin the cycle again — earning trust, meeting basic needs, advocating for education, empowerment, and eventually, understanding, self-sufficiency and change.

Sponsors play a critical role in moving each new family in a positive direction.

As Vaishali asks the women about the impact of sponsorship and the DEESHA on their families, a mom in a white sari stands to speak.

“Because of our economic condition, we couldn’t educate our children the way they are being educated now,” she says. “We are very grateful to sponsors who help without even seeing them.”

Today, almost all parents agree that their children should go to school — even their daughters. And they are amazed that someone across the world cares enough to help.

“I am not educated at all,” says Raju, the dad who sleeps outside his home so there’s room for his family inside. “I think it is good that the children are going to school, even though I can’t understand it.”

Children are dreaming beyond their circumstances — they want something more for their life. But their dreams for their future — wanting to be an engineer or a police officer or doctor — also reveal a difficult truth.

“They want to be these things because they have seen lots of suffering and want to do something about it,” Vaishali says. “If they say they want to be a police officer, [that means] they have seen domestic violence, and experienced a police officer fixing the problem. So they want to bring the family out of that problem. If they want to be an engineer? They want to build a better house for their family.”

And most of the children who said they wanted to be doctors? They’ve gone through the trauma and grief of losing a parent to an accident or illness.

It’s an hour before final exams and we visit a quieter neighborhood in Pune. Again, we go door to door; most of the families living here are sponsored families, too.

Many children from this neighborhood attend an all-girls school just blocks away where over 250 students are enrolled in Holt sponsorship. Sponsorship at this school began in just 2016, but already, the dropout rate has decreased, and enrollment has increased.

Families now want to send their daughters to school. But they face one consistent roadblock: cost.

The cost to send one child to government school for one year — including school fees, a backpack, school uniforms, books and school supplies — is 2,000 rupees, or just over $27. To most families living here, $27/year is still an insurmountable amount without the support of sponsors.

The first house we visit in this neighborhood is Harshada’s. Thirteen years old, she is very shy. Her 7-year-old brother grins impishly from the bed where he sits with their grandmother.

Harshada wants to be a police officer; she wants to help people in emergencies. Then we learn why.

Up until a couple years ago, Harshada suffered from epileptic seizures. Sometimes it was so bad, the caretaker at her school would have to carry her home in the middle of the day so that her parents could take her to the hospital.

The family is still paying her medical bills, and if it weren’t for her sponsor, Harshada’s family could not have afforded the fees, supplies and uniform she needed for school. She may not even have been able to attend school at all.

We walk next door to visit another family. A long, skinny corridor opens up to their home, made up of three small rooms stacked on top of each other. Yellow wallpaper brightens the windowless room. Three sponsored children — two sisters and their cousin — live here.

Without sponsorship, school would not have been possible for the three kids in this family.

“Before getting sponsorship, we were finding it difficult,” says a woman wearing a kurta with red and white roses on it, mom of the two sisters living here. “But then after sponsorship, we are finding it good and we are happy to be a sponsored family.”

Like so many families living in the slums, this mom and her children share their cramped living space with more family members. The sisters’ cousin, 15-year-old Jaya, also lives here with her parents. She wears a royal blue and white collared dress that beautifully compliments her dark skin.

“I want to be a police officer,” she says. “If anyone has a conflict or fight, I want to solve those problems of the people.”

Vaishali asks her if she has witnessed the police breaking up a fight, and Jaya slowly nods.

“A girl should be a police officer to save the girl child, and women,” Jaya says. “To empower them. To make them more strong, and to feel good about themselves.”

Until recently, the idea of any child from poverty — especially a girl — dreaming of this type of job was unheard of. But Jaya knows it’s time for a change. And she wants to be a part of it.

Final exams start in just a few minutes, so the girls put on their uniforms, and start walking to the school.

It’s a couple hours later, and the girls are done with their exams. Harshada, Jaya and other girls gather on the steps in their school’s courtyard with their mothers.

“I feel proud of my daughter,” one mom says about sending her daughter to school.

“It is good for her,” another says.

They begin talking about school, about how they want their daughters to have proper jobs — perhaps one with a chair and a table to work at. Not hard, manual, unskilled labor type of jobs like the ones they’ve had to work.

From here they delve into all the ways they want their daughters to have a better life than they’ve had. They want them to wait until they’re at least 18 to get married. They want them to have good husbands who aren’t violent. They want them to be self-sufficient. And they know that education is the singular best way to ensure these things.

“Education helps prevent young girls from getting married early,” Roxana says. “While I won’t say it’s changed, I will say it’s changing, and we’re trying to see how maybe we can help the mothers to get the girls more independent. To stand on their own feet, and then get married.”

Because of sponsorship, so much is changing in India. Living conditions are safer. Girls are getting married later, and completing their education. And both boys and girls are empowered to dream beyond their circumstances.

Despite the cramped slum communities where they live, and domestic violence, and illness and gender inequality, they dream of a better future.

Perhaps not everything is changed in India. At least not yet. But because of sponsorship, things are changing.

Become a Child Sponsor

Connect with a child. Provide for their needs. Share your heart for $43 per month.