For women and children at risk of abuse in India, Holt donor and sponsor-funded education programs are helping to prevent violence and help moms and children escape abuse.

Even at night, when Raji’s father pulls the string switch to the single light bulb in their one-room house and her surroundings go dark, there is no privacy.

A single trickle of orange street light flickers in through a crack under her tin door, and with the faint glow of light, Raji can see her two brothers as they shuffle and roll on the floor next to her, trying to get comfortable. She can hear and see her parents as they climb into their iron-framed twin bed, settling into sleep.

Sometimes her father stays awake, leaving to smoke a cigarette in the alley, and she can hear his muffled voice as he laughs with the neighbor men. Raji can hear a dog barking in the distance, the sound of a neighbor dumping their bucket of wash water into the thin alley. She hears a baby crying, the son of one of the girls in Raji’s class who was married last year and then dropped out of school. She and her husband moved into a tiny room two floors above her.

Raji wonders if this will be her soon. She knows her mom wants to find her a husband. She counts on her fingers the months until her 13th birthday, the age her mom says she will start looking for a husband. Only four months left.

Raji does not want to be a wife. At least, not yet. She wants to be a doctor in a long, white coat with a stethoscope around her neck. If she’s a wife, she’ll never have a chance to go back to school, to wear the crisp skirt and button-up shirt of her uniform.

What Raji doesn’t know is that not only is early marriage likely to end her chance at an education, but also increase her risk of being abused, and of raising her children in an environment where their odds of being abused are also high.

In India, especially in impoverished urban and rural communities, domestic violence, sexual assault and abuse is problematic, in part because of how common it is, but also because there are few options for female and child victims to fight back or escape. Abuse is normalized further by the fact that neighbors may know a woman is being abused, yet never speak about it, and compounded by other cultural norms, like girls forced into marriage before they have grown into adults themselves.

For both women and children, abuse and gender-based violence can have lasting consequences. Children who witness violence and abuse are more likely to be abused themselves, or to grow up to abuse others. It’s a cyclical problem that spans generations.

But many women and girls do not even understand that what they are experiencing is abuse and that they have the right not to be abused — a fact that’s hard to understand in the West, but completely understandable in a country where women are often treated as second-class citizens. With one of the highest rates of illiteracy, especially among families living in poverty — and especially among women living in poverty — women also do not have easy access to information about their rights. Across India, education campaigns to raise awareness about violence and the rights of women and children are rare.

Rare, but not non-existent.

In Pune, India, Holt’s partner Bharatiya Semaj Seva Kendra (BSSK) is working to end violence against women, one neighborhood at a time.

At a community center that serves more than 842 children and teens in the area, a group of more than 50 boys and girls 12-14 years old sit in groups of five or six all around the room. They are chatting loudly, occasionally giggling. Around the room, you can see boys and girls turning red in embarrassment or collapsing into a fit of laughter on their friend’s shoulder.

They are discussing whether a girl who wears a short skirt deserves to be raped.

This is one of three summer camps at the community center, a donor and sponsor-funded week of activities for children from high-risk families and communities, aimed at personal development, sexual education and career and marriage preparation.

While the question may seem candid and overly complicated for a group of children so young, Vaishali Vahikar, the director of sponsorship at BSSK who oversees the DEESHA (Development of Education Environment Social Health Awareness) Community Center, knows that this is the critical age to engage children in conversation. The boys are young enough that many of their female classmates are taller than them. They still feel silly and embarrassed when they talk about dating, much less a much more serious topic. And yet, Vaishali knows, many of the young girls in the room could be married at any time. Most will be married before they are 16. For many of these children, this summer camp may be the only time they are taught to treat women as equals, and Vaishali hopes the message will stick.

In the evenings, Vaishali and her team of teachers walk children to their homes. They are common figures in the Pune communities where 700 Holt-sponsored children. In addition to running after-school activities and summer camps, they also make sure children who receive school fees, uniforms and supplies from their Holt sponsors in the U.S. are living in safe environments. They do all they can to keep children, but especially girls, in school.

They are worried about Rajeshree. She hasn’t even hit puberty yet, but convincing her mom she is too young to marry has proved tricky.

“The first time we met with Raji’s mom, she told us that she was married at 13 and had her first son at 14,” Vaishali says of the conversation with Rajashree’s 35-year-old mother. Raji’s oldest brother is 21, and he married this year.

“Why should my daughter be any different?’” Raji’s mom asked Vaishali.

There is a direct correlation between education level and poverty in India, and while domestic violence and abuse is common across all classes, Mary Paul — the now-retired (and much beloved) former executive director of Holt’s long-time partner in Bangalore, Vathsalya Charitable Trust — describes violence against women as rampant in impoverished communities.

“The girl is always viewed as less,” Mary Paul says. “Abuse starts at a young age, even as young as 3. And it is not talked about because it is so shameful. Many women think it is their fault when they are abused.”

Holt’s director of India programs, Bhumika Tulalwar, says that the key to keeping women and children safe from abuse is education. Educated girls are more likely to earn a higher income, access safer housing and medical care, and be taken more seriously if they ever report a crime. And, while a higher level of income or socioeconomic status does not necessarily mean a woman will never encounter domestic violence, it certainly improves her odds.

“Women experience domestic abuse from their husbands, in-laws and family members,” Bhumika says. “Although domestic violence occurs in all settings, abused women from the slums face distinct barriers to obtaining support and services. Slum environments are characterized by low socioeconomic status, unhealthy living conditions, and a lack of basic services. These aspects play a role in women’s vulnerability to abuse and their inability to break free from abusive relationships. Factors that enhance the stress level of families have been shown to increase the probability of domestic violence, especially in slums.”

Bhumika says various, interwoven factors or behaviors make a woman from an impoverished community more likely to be abused, including failing to perform gender-based duties, like housework and child care, talking to strangers without the permission of her husband, economic stress, illiteracy, not having a male child, her age at marriage, her employment status or job, belonging to a lower caste or even her dowry.

While abuse is never okay for any reason, Bhumika says women’s abusers often make them feel like they deserve to be abused — a pattern that’s common everywhere, not just in India. But Holt staff and child advocates are determined to teach women otherwise, and trained to intervene when they see or hear about a child or his or her mother being abused.

“We have to educate women that how they are being treated is not ‘normal.’ It’s not their fault, and they shouldn’t have to continue to suffer,” Bhumika says. “We also educate women about the resources available to them if they choose to say no to their abuser. Through educational and employment opportunities, programs like the DEESHA help women break free from abusive relationships.”

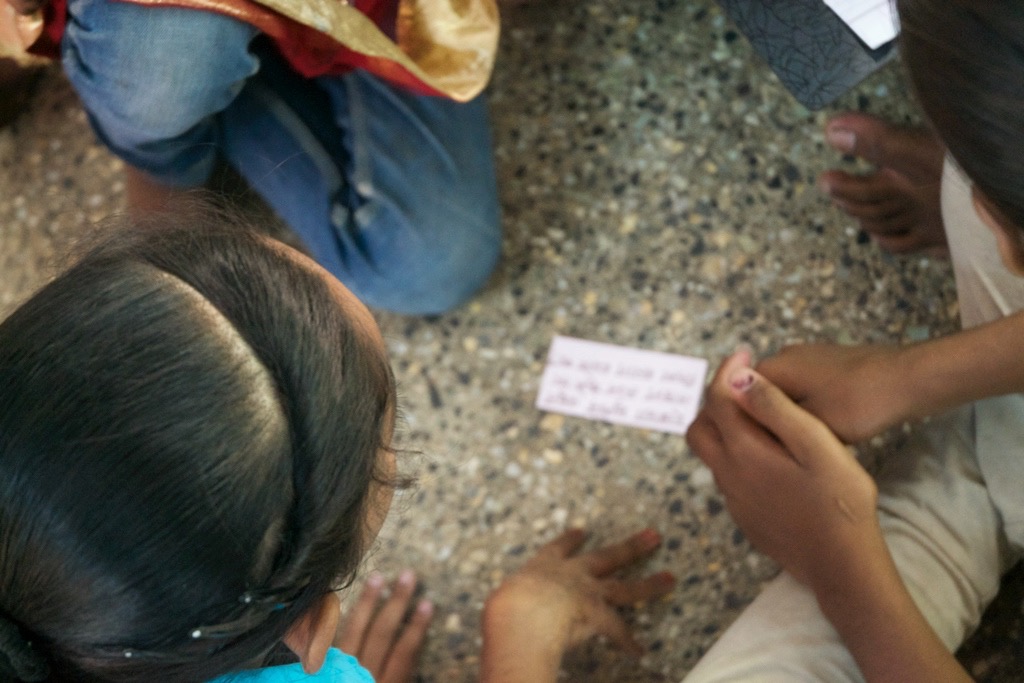

For women or children facing abuse, their advocate will increase the number of visits and follow-up visits to the child’s home. They will help set up appointments at local clinics, or invite mothers to come together in community groups. In parent training classes, which are open to both moms and dads but much more heavily attended by mothers, they will openly discuss how to identify and report abuse, which helps women in the community reach out to friends who may be experiencing violence. Through guided activities, the community group may brainstorm ways to stop abuse and gender discrimination in their communities — such as creating documents with emergency helplines, legal resources, shelters and other community resources available in formats understandable to women who can’t read.

Funding from Holt sponsors also provides family counseling to moms and dads who may otherwise not be able to afford such services. Through anger management or partner counseling, Holt advocates and social workers can help women regain their confidence and sense of individuality, and help reduce or stop violence in the home.

But most critical is stopping abuse before it ever starts. Through education, Holt’s partners believe generational change is possible in India.

And it starts by fighting to keep girls like Raji in school as long as possible.

“I tell moms now that their daughters don’t have to be like them,” Vaishali says. “I tell them that they can get good jobs. They can marry later. For many of these families, they need money now, so it’s hard to see how it will pay off to keep their girls in school, but that’s what we teach them.”

Some moms are totally on board. They regularly attend parent training at the community center, where they can even receive a certificate for completing the parenting course, which includes a section on reporting abuse. Parents and children are also trained about how to respond if they see a child being abused, which creates a community of informed and prepared parents and watchful eyes.

“We’ve seen very good results from the program,” Vaishali says. “Because families in these communities live in such close quarters, it means that children can accidentally be exposed to things they shouldn’t see. Or they have no privacy, even from their family. It’s part of the reason that abuse is so common. But, it also means that these are close-knit communities. The neighbors all know each other, and can help keep each other safe. They can talk about what behaviors to avoid in the home, too, so children aren’t exposed to such things.”

However, raising awareness isn’t always enough, and with that in mind, the programs that sponsors support in India have extra stipulations to protect girls. Female students are given sponsorship and school scholarship preference in the communities where Holt works in India. While boys are equally deserving of an education, parents will often do everything they can to keep their boys in school, but pull their girls out early to be married or begin working. For families with both boys and girls in the home, every child in the family is matched with a sponsor and receives a scholarship, but only as long as their daughter is allowed to stay in school.

For Raji’s family, the fact that her two younger brothers attend school for free may be the main reason she is allowed to stay. While that’s a tough reality, Vaishali knows that some day, even if Raji marries young, staying in school as long as possible will empower her to protect herself and her children — and with a heightened appreciation of the value of an education, maybe Raji will also one day advocate for her own daughters to graduate from school. But Vaishali and her staff are determined not to let Raji get married off before she is of age. The legal marrying age for girls in India is 18 (21 for boys). If Raji’s parents try to break this law, her advocate will report them to the police.

At camp, Vaishali quiets the group of students. “So,” she asks, “What do you think? Do girls in short skirts deserve to be raped?”

Across the room, boys’ and girls’ hands shoot up.

Vaishali calls on a boy with bright, sparkling green eyes and a red shirt.

“Of course not,” he says, confidently. “Nothing a girl wears means she deserves to be raped.”

All the children’s hands drop once he finishes speaking. This is not a question that needs further debate.

“This is what I hope these children learn,” Vaishali says, smiling at her pre-teen student’s response. “I want boys and girls to know that being the victim of abuse is never their fault. And I want boys to learn not to abuse.”

Billie Loewen | Creative Lead

Give a Gift of Hope

Give a lifesaving or life-changing tangible gift to a child or family in need. And this holiday season, give in honor of a loved one and they’ll receive a free card!